The modern space industry is witnessing exponential growth in small satellite and nanosatellite areas. Nanosatellite and microsatellite refer to miniaturized satellites in terms of size and weight, in the range of 1-10 Kg and 10-100 kg, respectively. ‘CubeSat’ is one of the most popular types of miniaturized satellites. These are the fastest-growing segments in the satellite industry. It is expected that the numbers of satellites in orbit are going to increase more than linearly with about 8000 spacecraft in orbit in 2024 due to constellations only. Over 2500 nanosats are estimated to be launched in 2021-2027.

The growth in small satellites is driven by the miniaturization of electronics and sensors and the availability of high-performance commercial off-the-shelf components, significantly reducing the cost of hardware development. The other rationale for miniaturizing satellites is to reduce the launch cost; heavier satellites require larger rockets with a greater thrust that also have a greater cost to finance. In contrast, smaller and lighter satellites require smaller and cheaper launch vehicles and can sometimes be launched in multiples. The access to orbit and economy of these spacecraft is also improved through the availability of secondary launch payload opportunities, especially for small satellites which conform to standardized form factors. They can be launched ‘piggyback’, using excess capacity on larger launch vehicles.

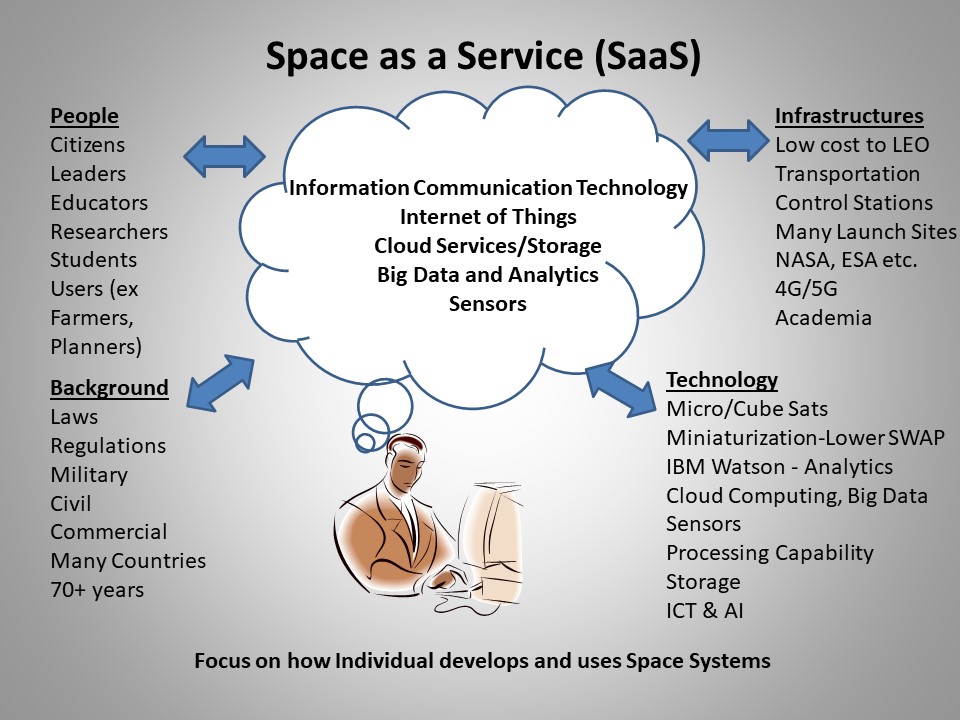

As the space sector expands, companies large and small are adopting new business models, including Space Data as a Service, Satellite as a Service and Ground Station as a Service, These new models are emerging as the space sector is witnessing large commercialization of satellite applications, which has opened new opportunities through the use of small satellites, on-orbit servicing, and low Earth orbit constellations. These services promise the benefits of space without the demands of satellite manufacturing, government regulations, launch integration or space data delivery.

The software technology sector has been shifting from an upfront customer purchase to a service model – Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) — for years now. Using the cloud and a baseline subscription service model, the sector achieves steady recurring revenue, high customer renewal, and scalability. In turn, customers access the exact solutions they need, avoiding upfront costs and risks. One of the most successful variants in the SaaS market is called “vertical software,” which focuses offerings on very specific industry segments such as healthcare or construction. The space sector is beginning to catch up to some of these trends in the wider technology arena, beginning with the purchase of subscription services (OpEx) rather than the purchase of hardware (CapEx).

However, there are a few unique structural aspects to space businesses. Terrestrial-based businesses can deploy an application to the cloud with relatively small upfront investments. This allows them to quickly reach first revenue. Driving growth beyond that requires significant ongoing capital investment for scaling of sales and marketing resources. Space businesses, on the other hand, require high amounts of early capital to deploy the satellites and other technologies on the ground before the network is in place to allow first revenue. They are then able to scale quickly with high margins and decreasing capital requirements.

This is beginning to change, the categorization Space-as-a-Service has been increasingly used over the last three years by a wide swath of companies to denote the provision of services instead of purchases related to satellites, ground stations, and ultimately specific, proprietary data delivery. The sector is now maturing to make data available to companies across verticals to deploy applications to space just as they deploy them to the cloud. It is a new maturity for the sector. Ultimately, this kind of offering needs to reach the point where a non-expert customer receives an API key to control their space application through software, and then pays a monthly fee for the access

Satellite-as-a-service

Satellite-enabled services can greatly improve global operations and provide near real-time information to improve decision-making processes. Examples include dedicated communications systems on a global level, or independent monitoring of resources, assets, weather and climate. However, Owning and operating space infrastructure requires expert knowledge, dedicated teams and capital expenditures well before the results are tangible. This gap often creates a barrier in the adoption of innovative space systems in day-to-day operations even when small satellite innovations have drastically improved time-to-market and total cost of ownership.

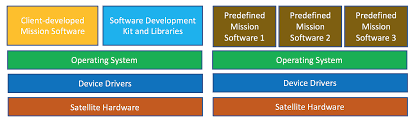

A shared-access, single host/multi-tenant satellite can dramatically lower the costs and speed up the development schedule of many areas of space technology, particularly related to the software area. This approach can also offer the ability to host multiple missions on a single spacecraft, sharing the capabilities of both the platform and payload instruments between multiple customers who can perform mission operations and experiments according to their needs.

“Satellite-as-a-service” solution is similar to “IaaS” (infrastructure-as-a-service) or “PaaS” (platform-as-a-service) offerings from cloud computing vendors. The primary business purpose of this platform is development and qualification service with the possibility of hosting customer-developed applications subject to platform capabilities.

Ground As a Service

The same economies of scale that benefit satellite customers are evident in the ground segment. “We offer a much more affordable price because we operate 100,000 satellite passes a month,” said Katherine Monson, CEO of KSAT Inc., the U.S. arm of Kongsberg Satellite Services of Norway. “Companies with a smaller volume have to divide their fixed costs fewer ways.” AWS Ground Station and Microsoft’s Azure Orbital advertise their ability to handle satellite command and control as well as data downlink through Ground Station as a Service.

Satellite operators who request time on an Azure Orbital antenna, for instance, send data directly to the Azure cloud. “You can use our fiber network to move data around the planet at a fraction of what it might cost if you were to do it yourself as a space provider,” said Tom Keane, Microsoft Azure Global corporate vice president. “When you combine the technology that existing players have with the technology that we have as a cloud provider, you can do some pretty amazing things.” Cloud services have helped reduce the cost of establishing a space company because startups don’t have to build their own data processing and storage infrastructure.

“Mission-as-a-service” or “software-defined satellite” similar to the “SaaS” (software-as-a-service)

“Mission-as-a-service” or “software-defined satellite” similar to the “SaaS” (software-as-a-service) solutions in the IT industry. With this level of service, more capable satellite hardware and software tools will become available, customized for the client’s needs. A number of different missions can be executed on this type of satellite platform, depending on the available payload instruments and subsystem capabilities. A single satellite can also host multiple instruments with sufficient capabilities to allow customers to run their software packages in parallel.

The major difference between those service types is illustrated in the diagram below, being that in a “satellite-as-a-service” platform, the customers are responsible for the development of the entire suite of mission software, while for the “mission-as-a-service” platform they would already have multiple ready-to-use software packages to run and operate, depending on the selected mission type.

Both types of service can be scaled up to meet any level of customer demand, using either more robust hardware for subsequent satellite generations or increasing the number of satellites in the orbital constellation and ground stations to improve communication coverage.

LeoLabs of Menlo Park, California, created an analytics platform that ingests data from the company’s global network of phased array radars tracking objects in low Earth orbit. Through the LeoLabs Platform, customers can search for satellites, see traffic patterns and receive warning when spacecraft are at risk of colliding. Software as a Service was first made possible by massive server networks and later extended by cloud infrastructure. Falling satellite and launch prices, the proliferation of ground stations and, in LeoLabs’ case, satellite-tracking radars cleared the way for Space as a Service.

An important benefit of the service model for space companies is scale. It’s expensive and time-consuming to purchase a single satellite and establish the ground segment and operations staff to gather data or relay communications. “Your entry cost is dominated by the fact that you have to do everything from the ground up,” said Walter Scott, Maxar executive vice president and chief technology officer. “There are opportunities instead to spread that infrastructure cost across a large customer base.” In addition, subscription service providers reap the rewards of a large customer base. “We can sell imagery and data feeds multiple times to multiple clients,” said Will Marshall, Planet CEO and co-founder. “The incremental cost to sell a data feed to a second user is almost nothing.” Venture capitalists are well aware of the benefits, having profited in many cases from investing in Software as a Service.

Space-as-a-service for Military

The Center for the Study of the Presidency & Congress released a new report May 2021 calling on the U.S. government to accelerate the procurement of commercial space technologies through “space access-as-a-service” model.

CSPC pointed at the Space Force’s Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared satellites as an example of how space acquisitions should not be done. “Five satellites to be deployed by 2028, the earliest of which may fly by 2025, at a cost of nearly $9 billion,” said the report. “This by no means leverages next-generation capabilities, mega-constellations, or other cutting-edge technologies.”

The group identified national security space launch (NSSL) as an area where the government could benefit from more competition. CSPC suggests DoD should buy “space access-as-a-service” and allow companies to qualify and compete for launches and in-space transportation contracts more frequently than the current NSSL program that selects providers for five-year deals.

“This model is proving successful for NASA’s Launch Service Program and should inform future planning for the Space Force,” said CSPC. The report noted that the National Reconnaissance Office is interested in using a more agile model of launch-as-a-service. “This model is proving successful for NASA’s Launch Service Program and should inform future planning for the Space Force,” said CSPC. The report noted that the National Reconnaissance Office is interested in using a more agile model of launch-as-a-service. Brett Alexander, vice president of Blue Origin, compared the NSSL program that only picks two providers for five years to a “high walled garden approach with all eggs in one, or now two, baskets.”

Such an approach allows the Government to benefit from increased competition amongst space access providers, with prices driven down but quality remaining high, as companies that fail to meet established standards and/or reliability will prove uncompetitive. This mechanism also allows the Government to incentivize performance. Bonuses could be awarded, for example, for vendors who get to orbit faster and with higher assurance, or who provide other additional capabilities

“We need faster development of more types of spacecraft and more launch options,” said Alexander. The Space Force should be “competing launches based on individual launches or small blocks, not these five-year, large contracts.”

References and Resources also include:

https://exodusorbitals.com/files/whitepaper.pdf

https://spacenews.com/space-as-a-service-model/