Traditional warfare is characterized as “a violent struggle for domination between nation-states or coalitions and alliances of nation-states. ” This confrontation typically involves force-on-force military operations in which adversaries employ a variety of conventional military capabilities against each other in the air, land, maritime, space, and cyberspace domains. The objective may be to convince or coerce key military or political decision makers, defeat an adversary’s armed forces, destroy an adversary’s war-making capacity, or seize or retain territory in order to force a change in an adversary’s government or policies.

Irregular warfare is defined as “a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant populations.” IW favors indirect and asymmetric approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capabilities to erode an adversary’s power, influence, and will. Rather than relying on traditional military action such as airstrikes and ground invasions, irregular warfare leans more heavily on digital deception and weapons that exploit holes in an adversary’s abilities. Traditional warfare and IW are not mutually exclusive; both forms of warfare may be present in a given conflict.

Irregular warfare is the oldest form of warfare, and it is a phenomenon that goes by many names, including tribal warfare, primitive warfare, “little wars,” and low-intensity conflict. They include civil wars in Rwanda and Somalia, guerrilla wars in Sudan, and rebellions in Chechyna; they involve irregular elements fighting against other irregular elements, regular forces of a central government, or an external intervention force. The modern hybrid or irregular conflicts are dominated by complex human dynamics with intertwining political, territorial, economic, ethnic, and/or religious tensions. States will continue to seek advantage through limited, irregular wars prosecuted through insurgency, resistance, coercion, and subversion.

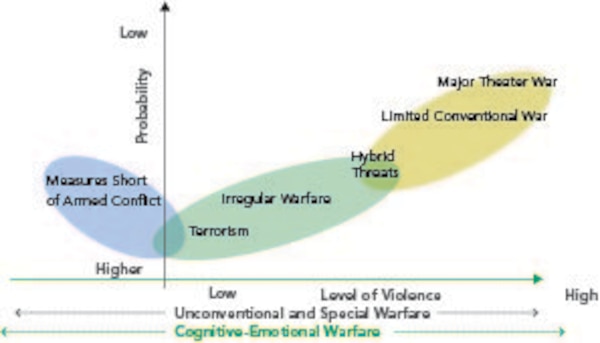

Irregular warfare favors indirect warfare and asymmetric warfare approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capabilities, in order to erode the adversary’s power, influence, and will. Irregular warfare is a long, attritional conflict, whereas, the world wars aside, conventional conflicts are often short, with a single conclusive battle or campaign. Differing levels of technology are most effective in each type of conflict. Because the weak do not have the capability to face strong actors conventionally, they complicate the environment by operating when and where they choose, with weapons that attack weaknesses of the strong and in a manner that leaves them often invisible to a stronger actor. They leverage loopholes in traditional notions of warfare to gain advantages against competitors and limit the potential for escalation to conventional conflict and/or major power intervention. The methods give primacy to psychological effects over physical destruction. They combine military and non-military instruments in a coordinated effort.

A newly published summary of an annex to the 2018 National Defense Strategy argues despite decades of asymmetric conflict—wars where enemies have exploited weaknesses in U.S. technology and tactics—the Pentagon is still underprepared for that kind of combat. The Defense Department says the entire military must get better at irregular warfare not just to fend off the rise of nonstate terror groups and cyber attackers, but to stymie Russia and China as well. The National Defense Strategy pivots the Pentagon to focus on potential conflict with those countries and other advanced militaries instead of lower-tech militants in the Middle East and Africa. The military must rethink how the joint force will use forces for counterterrorism and counterinsurgency missions as well as digital ventures like cyber and information warfare, DOD said.

“As we seek to rebuild our own lethality in traditional warfare, our adversaries will become more likely to emphasize irregular approaches in their competitive strategies to negate our advantages and exploit our disadvantages,” DOD said. “Their intent will be to achieve their objectives without resorting to direct armed conflict against the United States, or buy time until they are better postured to challenge us directly.”

To address the issue, the Pentagon advised more consistent investment in irregular warfare capabilities that are easily upgradable and cost-effective, to prepare for “gray area” conflict, like that in cyberspace, to escalate into the physical realm, and to put forth unified effort across the DOD and other federal agencies and allied and partner countries. The Air Force is overhauling how it organizes, trains, and equips offensive and defensive cyber forces and its intelligence-collection units to meet some of these demands. But while the service touts advances in areas such as artificial intelligence, it faces a significant struggle to maintain an inventory that can take on a world power and non-state actors with different resources and aspirations.

Success in irregular conflicts requires an understanding of the physical, cultural, and social environments in which they take place. Ethnicity is a powerful element in irregular warfare. Ethnic conflicts in Liberia, Rwanda, Burundi and elsewhere in Africa have led to appalling human and economic losses. In Kurdistan, there is continuous struggle within the Kurdish population based on tribal and family allegiances. At the same time, the Kurds are engaged in an ethnically based struggle against the Governments of Iraq and Turkey. Similarly, in Somalia an ethnically homogeneous population engaged in bitter intertribal/interclan conflict, making both de facto allies and enemies with external intervention forces.

Captain Robert Newson, former Naval Special Warfare strategy and concept commander, argued against continued high-tech solutions for such a low-tech enemy. He suggests the cost will be too great for prolonged irregular warfare using expensive high-tech weapon systems, while our enemies continue to see success through low-tech means. Using this high-tech strategy against a low-tech enemy has proved to be a complete failure. Hightech solutions have led to massive cost overruns and implementation delays, while ignoring the needs of the military forces brings the United States not a single step closer to ending the war on terror. These over-expenditures, multiplied over the course of a decade, have led to confined resource availability.This strategy, which emphasizes high-tech weaponry in irregular warfare, increases asymmetry between the strong and weak actors, but decreases both capability and effectiveness.

Innovative use of lower technology offers a more proportional and cost-effective solution while maintaining an operational or asymmetric advantage. The U.S. Air Force has recognized a problem with its employment of advanced technology, as they have noted in their irregular warfare doctrine that “[irregular warfare] is about right-tech, not about high or low-tech.” Three noted scholars suggested doctrine must be addressed to enable the technology transformation called for by the OSD. According to Richard Rubright, “Doctrine applied by military force is as important as the military devices themselves.” Moreover, Hone and Friedman postulate that any technology innovation is useless to the military components without a doctrine to exploit these advances or changes in technology. Additionally, this doctrine should be realized for building techniques and training to enhance technology employment capability and effectiveness.

Andrew Mack argued that popular and political will influence the outcome of irregular wars, often giving the weaker actors victory. As time progresses, strong actors suffer from falling popular support, which contributes to lost political resolve and forces the strong actor to abandon its engagement. Thus, weak actors need only strive to “hold out,” rather than achieve victory through a decisive engagement.

The 21st century technological advances are driving changes in the nature of warfare. These S&T areas include, nanotechnology, including meta-materials; robotics, including lethal autonomous systems; artificial intelligence and machine learning; the AI and cognitive neurosciences; biotechnology, synthetic and systems biology; directed energy weapons; additive manufacturing (aka 3D printing), space weapons, cyber and quantum technology. These new technologies may bring enhanced or entirely new capabilities. Many of these capabilities are no longer the exclusive domain of any of the state. Some of these technologies are also impacting irregular warfare.

Cyber technology and Artificial intelligence has become the most sought after means for waging irregular warfare. They serve as a tool for propaganda, phishing, and data manipulation, dissemination of information, identity theft and establishment of cyber physical weapons along with Advanced Persistent threats (APTs) to be used against critical infrastructure of states.

AI will drive an evolution in irregular warfare, where dominance in information and understanding can prove decisive by increasing the speed, precision, and efficacy with which information is wielded in these conflicts. Artificial Intelligence is also changing nature of irregular warfare because of its potential to significantly enhance intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. AI-enabled satellite imagery and remote sensing may help states to interpret each other’s actions correctly which may make nature of irregular warfare more complex and ambiguous.

There is also growing risk of non-state actors and groups gaining access to AI-enabled weaponry. In terms of proliferation risk, these weapons have unique appeal to non-state actors as they are relatively cheap to develop and easy to procure compared to weapons of mass destruction. In the future, Russian support to proxies in Ukraine could include the transfer of AI-enabled robotic improvised explosive devices to target key infrastructure or government leadership. Similarly, future offshoots of the Islamic State could develop AI capabilities that target, radicalize, and enable vulnerable individuals in the United States with hyper-specific propaganda built off of social media signatures.

We are also beginning to see AI-driven integration of real-time data, enabling a deeper understanding of behavioral patterns, relationships, patterns of life, and tradecraft. These capabilities offer the promise of allowing U.S. commanders to more quickly and effectively respond to adversaries’ irregular warfare capabilities by identifying, shaping, and disrupting subversive efforts in real time. Future applications of these technologies could involve, for example, automated identification of early warning indicators, or even predictive analysis of a population’s key vulnerabilities to adversarial disinformation.

AI will, however, make it harder for the U.S. military and intelligence community to operate in the shadows during proxy or undeclared wars. As facial recognition, biometrics, and signature management technologies become ubiquitous, it will become far harder to hide soldiers or equipment from adversaries or even private citizens. The U.S. military should prioritize new approaches to deception and signature management, as well as an emphasis on “counter-AI” capabilities that frustrate the efforts of its adversaries to use AI to uncover what it wishes to remain hidden, writes Daniel Egel of nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

There is need to recruit, develop, retain, and enable personnel capable of leveraging AI capabilities. This will require institutionalizing AI as part of irregular warfare doctrine, strategy, and tactics, and developing the training programs necessary to build the force appropriately. It will also require developing highly specialized, integrated teams that draw on the blended skill set of data scientists, operators, and intelligence professionals.

References and resources also include:

https://warontherocks.com/2019/10/ai-and-irregular-warfare-an-evolution-not-a-revolution/

International Defense Security & Technology Your trusted Source for News, Research and Analysis

International Defense Security & Technology Your trusted Source for News, Research and Analysis