Digital battlefields, hybrid warfare, and the future of threat intelligence

IDST Intelligence Briefings

(Latest Security & Cyber Videos)

Why This Magazine Exists

Security, Cyber & Counter-Threats examines the evolving landscape of modern security in an era defined by digital conflict, hybrid warfare, and persistent global threats.

From cyber operations, information warfare, and intelligence-driven defense to counter-terrorism, internal security, and emerging threat vectors, this magazine provides strategic analysis, technical insight, and policy-relevant perspectives for decision-makers, practitioners, and researchers navigating an increasingly contested security environment.

What We Track

- Cyber warfare & cyber defense

- Information operations & influence campaigns

- National security threat assessments

- Emerging digital and hybrid warfare doctrines

- Critical infrastructure & cyber resilience

Latest Analysis & Intelligence

-

Digital Fortresses: How DARPA’s CPM Program is Reinventing Cybersecurity Through Automatic Compartmentalization

In the relentless cat-and-mouse game of cybersecurity, defenders face a fundamental asymmetry: an attacker needs to find only one vulnerability, while defenders must protect every possible entry point. This imbalance has resulted in a constant stream of breaches dominating headlines and costing economies billions. DARPA’s Compartmentalization and Privilege Management (CPM) program seeks to change…

-

The Sky is the Limit: How Emerging Technologies Are Powering Urban Air Mobility

Imagine hailing a quiet, pilotless air taxi as easily as booking an Uber, soaring over gridlocked traffic to reach your destination in minutes instead of hours. This is the promise of Urban Air Mobility (UAM), a revolutionary transportation system poised to transform the way we move within and around our cities. As global urban populations…

-

SEAQUE: Pioneering Self-Healing Quantum Technology for the Final Frontier

How NASA’s autonomous quantum experiment is shaping the future of secure communications and resilient space infrastructure. In the harsh, radiation-filled environment of space, NASA’s Space Entanglement and Annealing Quantum Experiment (SEAQUE) is quietly redefining the future of quantum technology. Deployed aboard the International Space Station, SEAQUE demonstrates that quantum systems can not only survive orbital…

-

Navigating the Depths: The $4.1 Billion Offshore AUV and ROV Market Set for Robust Growth

Introduction: Exploring the Hidden Frontiers Beneath the Waves Beneath the ocean’s surface lies a vast and largely unexplored frontier — one that holds vital resources, energy potential, and scientific mysteries. To explore and operate in this environment, humanity relies on two classes of advanced underwater systems: Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs).…

-

Nanotechnology at Scale: Global Market Outlook and Strategic Opportunities (2025–2032)

Look closely—closer than the eye can see. In the realm of the nanoscale, where matter is measured in billionths of a meter, a silent revolution is underway. Here, scientists are engineering materials atom-by-atom, unlocking properties that defy conventional physics. This is the world of nanotechnology, and it’s transitioning from laboratory wonder to a foundational technology…

-

Forging Digital Shields: How Nations Are Using Cyber Ranges to Prepare for Modern Conflict

In today’s interconnected world, the battlefield has extended far beyond land, sea, air, and space—it now includes the invisible yet critical domain of cyberspace. Power grids can be disrupted from a distant server, financial networks can be infiltrated without warning, and military command systems can be compromised in mere seconds. The modern era of digital…

-

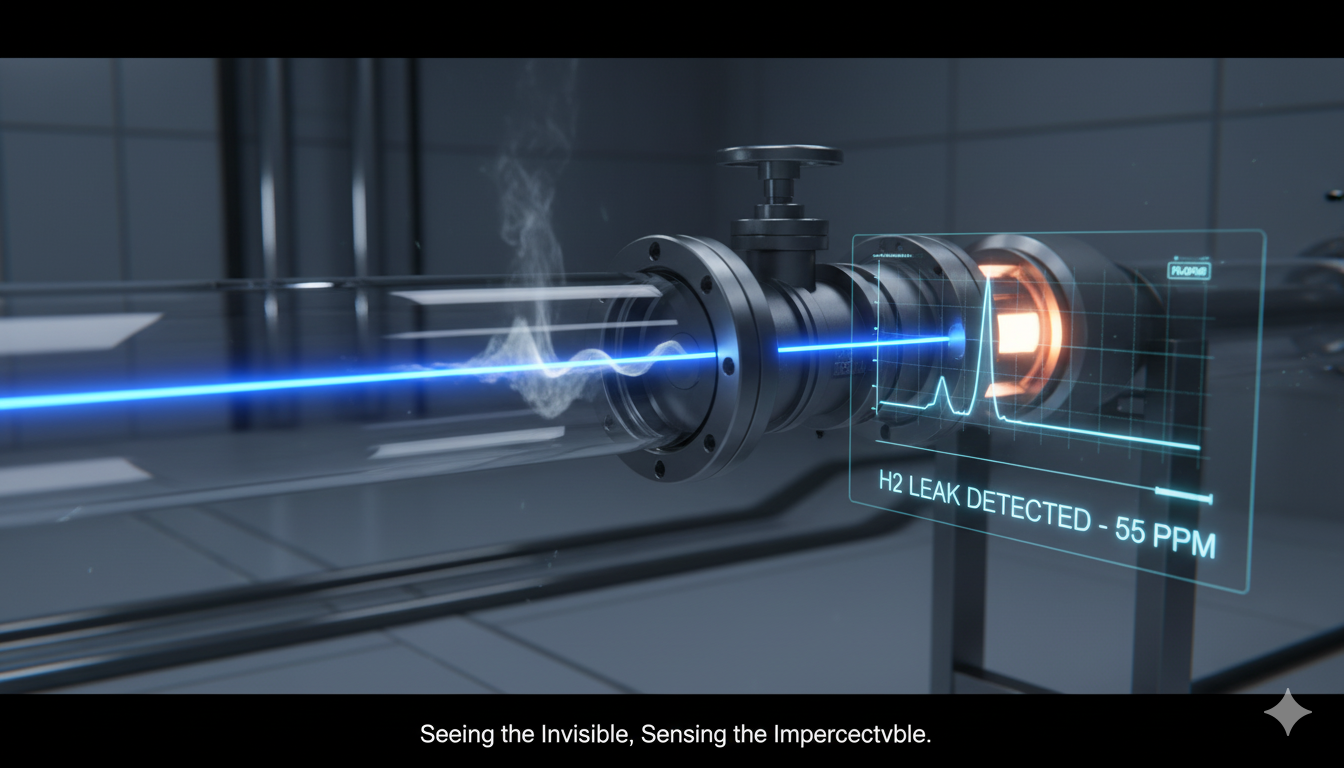

The Invisible Made Visible: A Look at Trace-Gas Sensing and the Hunt for Hydrogen

Introduction Breathing in the air around us, we seldom consider the invisible world of molecules drifting unseen—some harmless, others hazardous. Detecting trace gases at minuscule concentrations is not just a scientific pursuit; it is a necessity for ensuring safety, protecting the environment, maintaining industrial efficiency, and enabling the transition to clean energy. Whether it’s…

STRATEGIC SUB-MAGAZINES

Modern military power emerges from the interaction of platforms, people, doctrine, and integration across domains. The Defense & Military Systems magazine is structured into focused sub-magazines that examine how combat capability is built, sustained, and employed across air, land, sea, weapons, and human systems.

Cyber & Information Warfare

Industrial outcomes are shaped as much by incentives, policy, and market structure as by engineering. Price signals, investment cycles, and regulatory frameworks quietly determine which technologies scale, stagnate, or fail.

This sub-magazine examines how markets behave under strategic pressure—where capital flows, how demand signals distort decisions, and why some industries adapt faster than others.

Explore the Cyber & Information Warfare Sub-Magazine →

Security & Threat Management

Modern security is defined by persistence, coordination, and anticipation. This sub-magazine focuses on how threats are identified, mitigated, and managed across institutions, infrastructures, and societies.

Explore the Security & Threat Management Sub-Magazine →