The Arctic region encompasses the seas and land north of latitude 66.33° N. The Arctic Ocean is the smallest of the world’s oceans but is transforming due to its melting ice. Eight countries possess territories there: Canada, Denmark (through possession of Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the US.

As the Global warming is melting the Arctic ice, and opening up new shipping trade routes and real estate, intense resource competition over an estimated $1 trillion untapped reserves of oil, natural gas and minerals has started. Human activities have grown in the Arctic by almost 400 percent in the last decade, the U.S. board estimated, in terms of shipping, mining, energy exploration, fishing and tourism. Considering its geostrategic importance many countries including Russia, China and US are planning military presence to protect their interests.

Russia is acting quickly to become dominating Geostrategic and Military power in the Arctic. Russia has been carrying out rapid Arctic militarization by building New airbases, icebreakers, ground forces, missiles and and carrying out military exercises there. Russia’s new military doctrine signed into effect on December 26, 2014, identified Arctic as one of three geopolitical arenas that Moscow has deemed vital to national security. Russia isn’t alone in its Arctic ambition. The United States, Russia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland all lay claim to the area and its abundant natural resources.

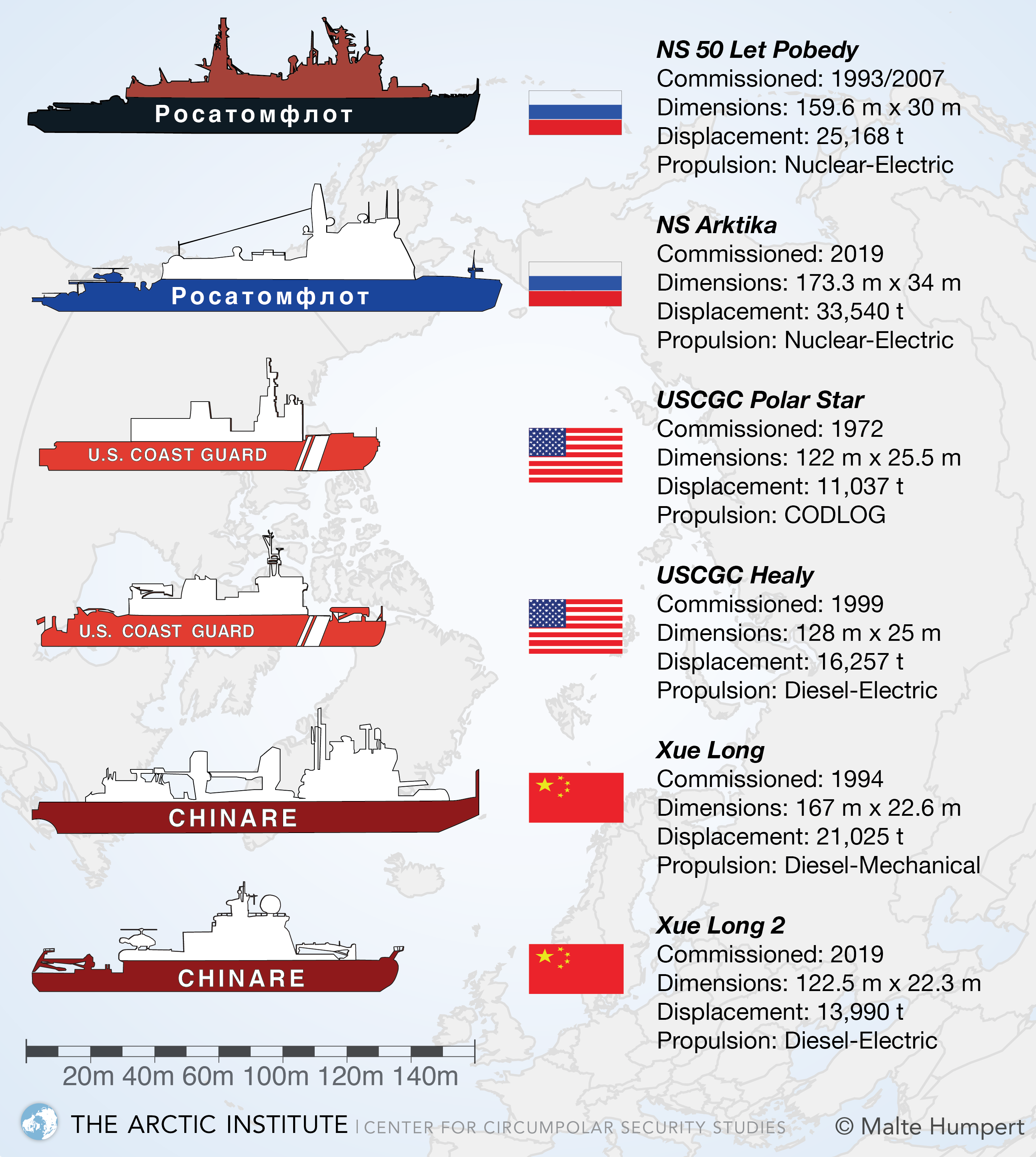

Russia has 53 icebreakers and Canada has seven, U.S. Coast Guard data show. These hulking ships are the basis for building the Northern Sea Route, or NSR. That route shaves off several thousand kilometers of navigation for ships plying the essential route from Asia to Europe.

In Nov 2020, Russian President Vladimir Putin attended the commissioning of a new diesel-electric icebreaker ship, the Viktor Chernomyrdin, which is the most powerful non-nuclear icebreaker in the world. Just two weeks prior, another ceremony announced the entry into service of an even larger and more formidable icebreaker, appropriately named Arktika. According to a report from the Russian-language newspaper Izvestiya, Arktika already sortied to the North Pole in early October, breaking through 3-meter ice en route.

Russia is the only Arctic country that produces nuclear icebreakers. But these extraordinary ships do not come cheap, with a price well in excess of $1 billion per hull. It is important, moreover, to see that the new Russian nuclear icebreaker is not a “one off” of purely symbolic significance. Two more of these ships, Sibir and Ural, are launched already. A fourth ship in this class, Yakutia, is now being built, while the fifth hull, Chukotka, will soon be laid down. In addition, preparations are underway in the Russian Far East to start building an even larger class of nuclear icebreaker.

Since then, thanks in part to its large icebreaker fleet, Russia has been able to renovate old bases and infrastructure. It claims to have built 475 new military sites, including bases north of the Arctic Circle, as well as 16 new deep-water ports. It secures this presence through sophisticated new air defense systems and anti-ship missiles. Russia also sees significant economic opportunities in offering icebreaker escorts, refueling posts, and supplies to the commercial ships that will ply the waterway.

China is the latest entry to have arctic ambitions. China has outlined its ambitions to extend President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative to the Arctic by developing shipping lanes opened up by global warming. Releasing its first official Arctic policy white paper in Jan 2018, China said it would encourage enterprises to build infrastructure and conduct commercial trial voyages, paving the way for Arctic shipping routes that would form a “Polar Silk Road”. The white paper said China also eyes development of oil, gas, mineral resources and other non-fossil energies, fishing and tourism in the region. It said it would do so “jointly with Arctic States, while respecting traditions and cultures of the Arctic residents including the indigenous peoples and conserving natural environment”. Like several other nations, China has established a research station in the Svalbard archipelago. China maintains a second research station in Iceland.

China thus far operates two medium-powered icebreakers and is building its third polar icebreaker. With three icebreakers, China could outpace U.S. icebreaker capacity and polar access by 2024. The primary concern with Chinese activities in the Arctic is the potential to disrupt the cooperation, stability, and governance in the region for both Arctic and non-Arctic states.

The United States has not commissioned a new heavy icebreaker in over forty years. Decades of looking past the vital importance of the Arctic has left our nation with only a single vessel of this class which is drastically beyond its service life. By contrast, all other nations laying territorial claims in the Arctic Circle each sustain a healthy fleet of icebreakers. This advantage may one day permit some of these nations to prevent the United States from accessing Arctic routes during a conflict, thus denying American commercial and national security vessels from transiting those waters, wrote US senators Marco and Rick to Admiral Karl L. Schultz , Commandant U.S. Coast Guard .

Icebreakers

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller vessels, such as the icebreaking boats that were once used on the canals of the United Kingdom. For a ship to be considered an icebreaker, it requires three traits most normal ships lack: a strengthened hull, an ice-clearing shape, and the power to push through sea ice.

Icebreakers clear paths by pushing straight into frozen-over water or pack ice. The bending strength of sea ice is low enough that the ice breaks usually without noticeable change in the vessel’s trim. In cases of very thick ice, an icebreaker can drive its bow onto the ice to break it under the weight of the ship. A buildup of broken ice in front of a ship can slow it down much more than the breaking of the ice itself, so icebreakers have a specially designed hull to direct the broken ice around or under the vessel. The external components of the ship’s propulsion system (propellers, propeller shafts, etc.) are at greater risk of damage than the vessel’s hull, so the ability of an icebreaker to propel itself onto the ice, break it, and clear the debris from its path successfully is essential for its safety.

Arctic waters do not necessarily have to be ice free to be open to shipping. Multiyear ice can be over 10 feet thick and problematic even for icebreakers, but one-year ice is typically 3 feet thick or less. This thinner ice can be more readily broken up by icebreakers or ice-class ships (cargo ships with reinforced hulls and other features for navigating in ice-infested waters).

Commercial ships would face higher operating costs on Arctic routes than elsewhere. Ship size is an important factor in reducing freight costs. Many ships currently used in other waters would require two icebreakers to break a path wide enough for them to sail through; ship owners could reduce that cost by using smaller vessels in the Arctic, but this would raise the cost per container or per ton of freight. Also, icebreakers or ice-class cargo vessels burn more fuel than ships designed for more temperate waters and would have to sail at slower speeds. The shipping season in the Arctic only lasts for a few weeks, so icebreakers and other special required equipment would sit idle the remainder of the year.

Militaries develop and deploy Icebreakers

The current state of the relative size of icebreaker fleets is best summed up in one diagram put out by the U.S. Coast Guard Office of Waterways and Ocean Policy. There are some key points to be seen here. Only the United States and Russia operate “heavy” icebreakers, indicated in black. Those icebreakers have the highest amount of power available to them, allowing them to operate in the thickest ice sheets. Of those heavy icebreakers, America only has one operational. Russia, on the other hand, has two operational with four more in refit. Once refits are complete, Russian heavy icebreakers will outnumber the American ones 3:1, providing Russia with better capability to run operations in heavy ice packs.

While the United States’ icebreaking capabilities have remained stagnant, Russia and China continue to advance policies and infuse resources into capitalizing the Arctic, including through the construction of additional icebreakers and intensifying economic relations across the region. China, in particular, without any Arctic borders, is following through with serious aspirations to fulfill its unsubstantiated claims to the region as a self-described “near-Arctic state.”

Russian Icebreakers

To support passage through the NSR as well as other civilian and military missions, Russia has undertaken a sustained build-up of its fleet of ice-cutters, including nuclear-powered ice-breakers that have more power and better endurance than conventionally powered vessels. Russian firms need them to support oil and gas transportation, and for rescuing distressed vessels and escorting other ships through the frozen waters of the High North. In the Arctic, these ships are the military equivalent of aircraft carriers in other oceans—the main symbol of national power projection and presence. Altogether, Russia has some 40 ice-breakers—more than the rest of the world combined.

Russia plans to add four nuclear icebreakers to its fleet so that by 2035, Russia will have a total of 13 heavy icebreakers, nine of them nuclear. In May 2019, Russia launched a nuclear-powered icebreaker at the Baltic Shipyard in St. Petersburg in an apparent attempt to boost its ability to tap the Arctic’s commercial potential. The icebreaker, dubbed the Ural, designed to be crewed by 75 people, is one of a trio, codenamed Project 22220, that when completed will be the largest and most powerful icebreakers in the world.

The 144-by-30-meter facility holds two reactors with two 35-megawatt nuclear reactors that are similar to those used to power the new icebreakers. The floating power station, or as it is called the “Chernobyl on ice”, can produce enough electricity to power a town of 200,000 residents. He said that these ships were also equipped with a brand-new Russian-made electric propulsion system. “And the most important thing is a new turbine which will provide 40-year operation for the icebreaker,” Kadilov added at a presser on Saturday. The two other icebreakers, dubbed the Arktika and the Sibir vessels, are currently under construction at the Baltic Shipyards.

The advanced icebreakers are powered by a new module nuclear reactor, which is far more powerful than those mounted on previous vessels of Project 22220, said Baltic Shipyards Director General Alexei Kadilov. He said that these ships were also equipped with a brand-new Russian-made electric propulsion system. “And the most important thing is a new turbine which will provide 40-year operation for the icebreaker,” Kadilov added at a presser on Saturday. The two other icebreakers, dubbed the Arktika and the Sibir vessels, are currently under construction at the Baltic Shipyards.After being put into service, the trio will keep navigation in the Arctic open all year round, capable of breaking through ice up to three meters thick to make way for convoys of ships. They are also expected to help ensure transportation of hydrocarbons from the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas to Asia Pacific.

The nuclear-propelled icebreaker Vaygach is now distinguished as having the longest-operating power plant on a civilian ship, the operating company reported. The Vaygach was built in Finland in 1989 and was fitted with a KLT-40M nuclear reactor the same year at the Baltic Shipyard in St. Petersburg. The pressurized water reactor was initially rated for 100,000 hours of work, but sound engineering and proper maintenance allowed its safe lifetime to be doubled.

In Feb 2018, the Vaygach beat the record of 177,204 hours of reactor operation, which was set 10 years ago when the Russian nuclear icebreaker Arktika was retired, Atomflot, which operates the Vaygach, reported. The 21,000-ton ship is part of a two-vessel class along with its sister ship, the Taymyr. The reactor used by both ships was first tested by the nuclear-powered container ship Sevmorput, while its latest version is used by the Akademik Lomonosov, a floating nuclear power plant currently in construction.

The world’s first floating nuclear power plant is set to start producing power and heat in 2019. While the plant is already being tested, construction of the dock has begun on the Arctic coast in Russia’s Far East. The construction works on the dock, which will host the floating nuclear power plant ‘Akademik Lomonosov’, in the bay of the city of Pevek, Chukotka, RIA Novosti reports. The severity of weather conditions (in winter, the temperature drops down to minus 60 degrees Celcius) obliging, the onshore facilities will be forced to endure ice impact and squalling winds.

Russia New Arktika Icebreaker

Arktika, the first of Russia’s new nuclear-powered Project 22220 icebreakers, the largest and most powerful such ship in the world at present, has set sail for its future homeport in Murmansk with plans to plow through ice in the Arctic before it arrives there. However, only two of the ship’s three engines are presently working, raising questions about just how close it really is to fully entering operational service.

The icebreaker utilizes a variable draft design allowing it to operate in the deeper waters of the Arctic Ocean, but also navigate shallow coastal areas and rivers. The nuclear-turbo-electric propulsion generates more than 81,000 horsepower – nearly twice as much as the planned new U.S. icebreaker – enabling them to break through up to three meters of ice and travel on most of the NSR year round. “It is with the ships of this series of new generation of icebreakers that we associate hope with the development of the Northern Sea Route. This is a fundamentally new ship,” explained Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov during the launch ceremony last year.

Construction of Arktika, the lead vessel in a fleet of five planned new nuclear icebreakers, has faced ongoing delays. United Shipbuilding Corporation was awarded the construction contract in 2012 for commissioning in 2017. However technical challenges, including with the construction of a domestically-built steam turbine, resulted in a three-year delay. The ship is expected to operate in the Barents, Pechora and Kara Seas, as well as in shallow waters of the Yenisei estuary and Ob Bay.

Although Arktika suffered from a damaged starboard propulsion motor, the vessel was commissioning with a reduced power output before extensive repairs in 2021, Kommersant Newspaper reports. During sea trials it was revealed that the ship’s right propulsion unit, a massive motor weighing 300 tons, was faulty and would have to be replaced. Nonetheless, the vessel continued mooring and sea trials successfully launching nuclear reactors and steam turbines. The United Shipbuilding Corporation, where the vessel was built, confirmed that the damaged propulsion unit can be operated at reduced power. As a short-term work-around the ship will likely be launched at reduced power output of 40-50MW rather than the full 60MW. The final decision to continue with more advanced sea trials and place the ship into service remains with the Russian government.

The faulty propulsion motor will then be replaced during a length stay in drydock in Kronstadt in 2021. Experts say the challenging replacement will likely take several months and may involve cutting a hole into the starboard side of the vessel through the ballast tank to gain access, remove, and replace the motor. Experts initially feared that the ship wouldn’t be able to get any power output from the damaged propulsion motor leaving the starboard propeller vulnerable to damage from ice pieces when moving through ice-covered waters. Whenever a vessel travels through ice propellers should be turning to ensure that the blades strike ice with the strong leading edge.

Even with a reduced output the vessel should still be plenty powerful for advanced sea trials and possible duty along the NSR this summer. In fact, with an output of 40-50MW, it will still rank among the most powerful icebreakers in operation. The exact cause of the damage will only be known after disassembling the propulsion motor next year. An overvoltage when the unit was first powered on, a faulty connection, or failures during its manufacturing could all have led to the damage. Experts point out that the shipyard will want to closely evaluate the damage and take precautions to avoid similar issues in the future as four more vessels of the same type will be following by 2027.

China’s Arctic Ambitions

China appears to be interested in using the NSR to shorten commercial shipping times between Europe and China and perhaps also to reduce China’s dependence on southern sea routes (including those going to the Persian Gulf) that pass through the Strait of Malacca—a maritime choke point that China appears to regard as vulnerable to being closed off by other parties (such as the United States) in time of crisis or conflict. China reportedly reached an agreement with Russia on July 4, 2017, to create an “Ice Silk Road,”100 and in June 2018, China and Russia agreed to a credit agreement between Russia’s Vnesheconombank (VEB) and the China Development Bank that could provide up to $9.5 billion in Chinese funds for the construction of select infrastructure projects, including in particular projects along the NSR.

China thus far operates two medium-powered icebreakers. The first one, Xue Long 1 (Snow Dragon) was originally constructed as an ice-class cargo ship in Ukraine in 1993 before it was purchased and outfitted by China as a polar research vessel in 1994. In recent years has made several transits of Arctic waters—operations that China describes as research expeditions. The country’s first home-built icebreaker, Xue Long 2, was developed in 2012 with design support from Finland’s engineering company Aker Arctic. The vessel was constructed by the Jiangnan Shipyard between December 2016 and summer 2019, and entered service in 2019.

China, is building its third polar icebreaker and staked a claim as a “near-Arctic” state, further injecting itself into policy debates. China in 2018 announced an intention to build a 30,000-ton (or possibly 40,000-ton) nuclear-powered icebreaker, which would make China only the second country (following Russia) to operate a nuclear-powered icebreaker. At the time experts surmised that a nuclear-powered icebreaker could serve as a technology test bed to further develop nuclear-powered propulsion in large surface vessels, e.g. aircraft carriers for the Chinese Navy.

In December 2019, however, it was reported that China’s third polar-capable icebreaker might instead be built as a 26,000-ton, conventionally powered ship. (By way of comparison, the new polar icebreakers being built for the U.S. Coast Guard are to displace 22,900 tons each.). With a displacement of 26,000 tons and the ability to break through ice three meters-thick continuou sly at two knots, the Polar Class 2 vessel comes close to Russia’s latest nuclear-powered Arktika (Project 22220) icebreakers in terms of size and ice-breaking capability.

United States

For many, the United States is woefully behind, with serious implications for national defense. One of the most common and consistent metrics to make this case is a comparison of the numbers of U.S., Russian, and Chinese icebreakers. As Lindsay Rodman highlights, when comparing Russian military advantages relative to the United States in the Arctic, “the most often cited example is icebreakers.” By this standard, Washington is losing to Moscow — and it’s not even close. While Russia has at least 40 icebreakers in its fleet, China and the United States have two icebreakers apiece.

The operational U.S. polar icebreaking fleet currently consists of one heavy polar icebreaker, Polar Star, and one medium polar icebreaker, Healy. In addition to Polar Star, the Coast Guard has a second heavy polar icebreaker, Polar Sea. Polar Sea, however, suffered an engine casualty in June 2010 and has been nonoperational since then. Polar Star and Polar Sea entered service in 1976 and 1978, respectively, and are now well beyond their originally intended 30-year service lives. The Coast Guard has used Polar Sea as a source of spare parts for keeping Polar Star operational.

In Dec 2020 Congress passed a bill authorizing the addition of Coast Guard Polar Security Cutters for use as icebreakers, and an Alaska senator said the Trump administration is considering leasing an icebreaker owned by a Republican donor. The Coast Guard has two icebreakers, but only one is operating following an August fire that damaged the USS Healy. Ongoing construction work on a new icebreaker is not expected to be finished until 2024.

The United States Coast Guard uses icebreakers to help conduct search and rescue missions in the icy, polar oceans. United States icebreakers serve to defend economic interests and maintain the nation’s presence in the Arctic and Antarctic regions. As the icecaps in the Arctic continue to melt, there are more passageways being discovered. These possible navigation routes cause in increase of interests in the polar hemispheres from nations worldwide. The Coast Guard’s large icebreakers are called polar icebreakers rather than Arctic icebreakers because they perform missions in both the Arctic and Antarctic. Operations to support National Science Foundation (NSF) research activities in both polar regions account for a significant portion of U.S. polar icebreaker operations.

The Coast Guard’s medium polar icebreaker, Healy, spends most of its operational time in the Arctic supporting NSF research activities and performing other operations. Although polar ice is diminishing due to climate change, observers generally expect that this development will not eliminate the need for U.S. polar icebreakers, and in some respects might increase mission demands for them. Even with the diminishment of polar ice, there are still significant ice-covered areas in the polar regions, and diminishment of polar ice could lead in coming years to increased commercial cargo ship, cruise ship, research ship, and naval surface ship operations, as well as increased exploration for oil and other resources, in the Arctic—activities that could require increased levels of support from polar icebreakers, particularly since waters described as “ice free” can actually still have some amount of ice. Changing ice conditions in Antarctic waters have made the McMurdo resupply mission more challenging since 2000, according to congress report: Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress.

The United States polar icebreakers must continue to support scientific research in the expanding Arctic and Antarctic oceans. Every year, a heavy icebreaker must perform Operation Deep Freeze, clearing a safe path for resupply ships to the National Science Foundation’s facility McMurdo in Antarctica. The most recent multi-month excursion was led by the Polar Star which escorted a container and fuel ship through treacherous conditions before maintaining the channel free of ice. Without a heavy icebreaker, America would not be able to continue its polar research in Antarctica as there would be no way to reach the science foundation.

The US Coast Guard (USCG) has awarded five firm-fixed-price contracts with a total value of nearly $20m, in order to conduct early industry design studies and analysis for the purchase of the country’s next heavy polar icebreaker. The contract awardees are Bollinger Shipyards in Lockport, Louisiana; General Dynamics / National Steel and Shipbuilding Company, San Diego; Fincantieri Marine Group in Washington; Huntington Ingalls and VT Halter Marine in Pascagoula, Mississippi, US.

Without these strategic assets, the Coast Guard will be unable to fulfill all of its mission requirements, including agency support for the Department of Defense, the Department of State, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Some observers have expressed concern about whether the United States is doing enough militarily to defend its interests in the Arctic. Whether DOD and the Coast Guard are devoting sufficient resources to the Arctic and taking sufficient actions for defending U.S. interests in the region has emerged as a topic of congressional oversight. Those who argue that DOD and DHS are not devoting sufficient resources and taking sufficient actions argue, for example, that DOD and the Coast Guard should build ice-hardened surface ships other than icebreakers for deployment to the Arctic and/or establish a strategic port in Alaska’s north to better support DOD and Coast Guard operations in the Arctic, according to Congress report.

International Defense Security & Technology Your trusted Source for News, Research and Analysis

International Defense Security & Technology Your trusted Source for News, Research and Analysis