An artificial island or man-made island is an island that has been constructed by people rather than formed by natural means. Artificial islands may vary in size from small islets reclaimed solely to support a single pillar of a building or structure, to those that support entire communities and cities. Human-made islands aren’t a new phenomenon—some in East Asia date back to the 1600s—they’re now being considered as remedies for overpopulation and climate change across the world, and perhaps that shows how desperate the fate of humanity has truly become.

Extending south of China and ringed in by the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, and Malaysia is a 1.35 million-square-mile body of water known as the South China Sea. The South China Sea has become a stage for Hong Kong’s dystopic future wherein 1.1 million people, many displaced by a housing crisis, are expected to live on artificial islands within the next 30 years.

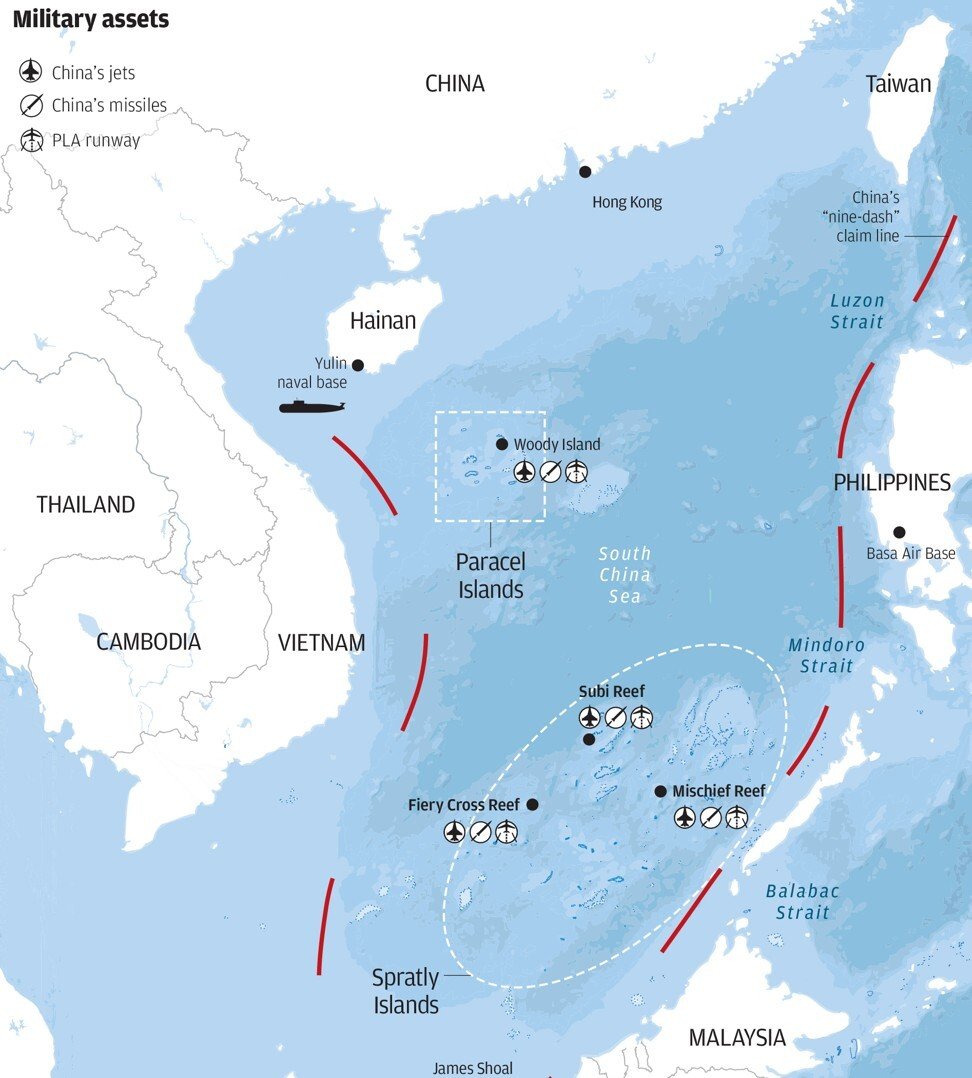

China has caused alarm among its neighbours and in Washington by constructing a series of artificial islands throughout the area on what were previously reefs and partially-submerged islets in the strategically-important waters. China has been transforming the reefs and atolls it occupies on the disputed Spratly Islands since 2015, turning them into artificial islands. The islands function as unsinkable aircraft carriers and help to cement Beijing’s claims on waters rich with fish and minerals, waters that neighboring countries also claim. It has also built airstrips and other military facilities and deployed equipment such as anti-aircraft guns and close-in weapons systems, according to the US think tank the Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

China has built seven artificial islands in the South China Sea and steadily expanded its military assets in this highly strategic area, through which one-third of global maritime trade passes. It has constructed port facilities, military buildings, radar and sensor installations, hardened shelters for missiles, vast logistical warehouses for fuel, water and ammunition, and even airstrips and aircraft hangars on the man-made islands.

Perhaps the most important installations sit on the Fiery Cross, Subi and Mischief reefs in the Spratly island group. Vietnam, The Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan all also claim the Spratlys.

China said the construction was intended to aid peace in the region, as well as maritime safety and disaster prevention. China lays claim to almost all of the South China Sea, through which more than $5 trillion (£3.8 trillion) of trade passes every year.

U.S. Navy Adm. Philip Davidson told the Senate Armed Services Committee that China can now control the South China Sea “in all scenarios short of war with the United States” because of its increasing military presence there. China has reportedly started to base some aircraft, including bombers, and missile systems on manmade islands in the region, causing concern among other Southeast Asian countries.

Artificial Islands

Early artificial islands included floating structures in still waters, or wooden or megalithic structures erected in shallow waters.

In modern times artificial islands are usually formed by land reclamation, but some are formed by the incidental isolation of an existing piece of land during canal construction (e.g. Donauinsel and Ko Kret), or flooding of valleys resulting in the tops of former knolls getting isolated by water (e.g. Barro Colorado Island). One of the world’s largest artificial islands, René-Levasseur Island, was formed by the flooding of two adjacent reservoirs.

Artificial island are mostly made of sand. To prepare the artificial island, a large amount of sand is required. This preparation of sand may cause environmental pollution. For example, Singapore dredged five hundred million tons of sand to prepare an artificial island. This sand removal caused desertification to a fishing town, having a bad effect on the ecosystem

In December 2013, the Chinese government pressed the massive Tianjing dredger into service at Johnson South Reef in the Spratly archipelago, far from the Chinese mainland. Between 2013 and 2016, huge construction vessels pulverized the reefs in order to create the raw materials for the bases. The dredger Tianjing alone shifted 4,500 cubic metres of materials every hour, “enough to nearly fill two Olympic-size swimming pools,” according to the Hong Kong South China Morning Post. The dredger’s job is to fragment sediment on the seabed and deposit it on a reef until a low-lying man-made island emerges. The Tianjing — boasting its own propulsion system and a capacity to extract sediment at a rate of 4,530 cubic meters per hour — did its job very quickly, creating 11 hectares of new land, including a harbor, in less than four months. All the while, a Chinese warship stood guard.

Beijing claims it has begun restoring the reefs it destroyed, but it’s unclear how effective restoration efforts might be. Marine biologist John McManus at the University of Miami said that dredging “kills basically everything” living around coral reefs. To the Chinese Communist Party, the new bases were worth the environmental cost. The installations “allow China to control the entirety of the South China Sea in any scenario short of all-out war with the United States,” The Economist explained. “The new port and resupply facilities are helping China project power ever further afield. Chinese survey vessels look for oil and gas in contested waters.”

Developing Artificial Islands in Denmark Could Lead to 12,000 Life Science Jobs

The government of Denmark is moving forward with a plan to build nine artificial islands on the coast of Copenhagen, The Guardian reported. When the artificial islands are completed, there will be space for an expected 380 companies, most of which are expected to come from the tech industry, according to the report.

The creation of the artificial islands will have a cost of about $480 million, according to Business Insider, and will provide approximately 10.5 miles of land to the Copenhagen coast. The project, if approved by the Danish government, would take about 18 years to complete. If given the greenlights, construction of the islands could begin by 2022. The expected date of completion would be 2040, according to the report.

Copenhagen is no stranger to artificial islands. Last year, plans were launched to build an artificial island that will provide housing for up to 35,000 people. Copenhagen is running out of usable space for housing and business and the construction of the artificial islands would be part of an answer to that issue.

When all is said and done, if it’s said and done as the government hopes, the project could provide approximately 12,000 jobs in fields like biotechnology and life sciences, according to the report. With an intense focus on technology companies, Brian Mikkelsen, Denmark’s Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs, told TV2 news in Denmark that the islands could become Europe’s version of Silicon Valley, The Guardian said.

Amid a housing crisis, Hong Kong’s government plans to create new developable land in the middle of the ocean.

Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, outlined a plan for the ambitious geoengineering project in a policy address in Oct 208. Dubbed “Lantau Tomorrow Vision,” it will add 4,200 acres of new land near Lantau Island, Hong Kong’s largest outlying island at the mouth of the Pearl River. The location was selected from a list of several potential sites. Hong Kong’s government has yet to attach a price to the project, but local media have estimated its total cost could reach $63.8 billion (HK$500 billion).

Lantau Tomorrow Vision will be Hong Kong’s largest land reclamation project, a process in which new land is created from bodies of water. Building an island out of nothing is no small feat—in Hong Kong, methods have included dredging the seafloor and injecting cement into the seabed. Approximately 6 percent of Hong Kong’s land is reclaimed, and houses 27 percent of its population.

“The vision aims to instil hope among Hong Kong people for economic progress, improve people’s livelihood and meet their housing and career aspirations,” Lam’s address said.

Hong Kong has had the world’s least affordable housing market eight years in a row, according to the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey of 300 cities. The average price per square foot is nearly $1,400 and one study found that Hong Kong’s apartments are, on average, the smallest in the world at 484 square feet. A shortage of developable land, dense population numbers—7.3 million people inhabit roughly 427 square miles—and an increasing demand to live in the booming technology hub are rapidly displacing residents who can’t afford a roof over their heads.

But environmentalists say the plan may irreversibly damage the surrounding ecosystem. Ecologists predict the islands could eliminate natural fisheries and disrupt ocean and wind currents. Noise pollution from construction could also harm the Chinese white dolphin, a local species whose numbers are already declining.

Another looming consequence is catastrophic flooding due to climate change. Sea levels in Hong Kong are expected to increase more than three feet above 2000 levels by the end of the century, Leung Wing-mo, former assistant director of Hong Kong’s weather monitoring observatory, told the South China Morning Post. Ringo Mak Wing-hoi, co-founder of the local climate change organization 350 Hong Kong, told the outlet that adapting infrastructure on the islands to resist sea level rise could double project’s total cost.

“If you want to minimize the chance of flooding, of course the higher [above sea level] the better,” Gabriel Lau Ngar-cheung, director of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Institute of Environment, Energy and Sustainability, said of Lantau Tomorrow Vision to the South China Morning Post. “But of course the cost will be far greater.”

Geostratgic and Military utility of China’s build-up of islands

The islands were fortified to create a network of small military bases, enforcing Beijing’s controversial territorial claims in the region and giving the Chinese military de facto control of the waters. Some bases are equipped to host China’s most powerful weapons, with 10,000-foot runways, hangars to house fighter planes and deepwater piers for warships.

In Dec 2018, nuclear-capable H-6K strategic bombers landed on some of the islands for the first time as part of a training exercise, putting all of southeast Asia within reach of Beijing’s nuclear fleet. The Chinese air force said the drills were in preparation for the “battle for the South China Sea.”

China has added a maritime rescue centre to its facilities on an artificial island in the South China Sea, pressing on with plans to turn the outpost into the biggest logistics hub in the disputed waters. The announcement comes six months after China stationed the Nanhaijiu-115 rescue ship at Subi Reef, another artificial island in the Spratlys.The rescue centre would provide stronger and more comprehensive support to rescue missions and would be part of the ministry’s “South China Sea rescue bureau” , the ministry said Yet Fiery Cross is only the third largest island that China ha sbuilt in the Spratlys – Subi and Mischief reefs are nearly double its size.

On the surface, these islands are hard to see as military bases at all. Given the size of the South China Sea, China could launch air attacks using manned or unmanned vehicles from bases on the mainland. Basing aircraft on these islands might give China a shorter time to reach some targets if it initiated conflict, but that advantage would quickly disappear. The islands are small, the number of aircraft that can be deployed on them is limited, and the first American response would eliminate them.

In November 2019 a surveillance blimp for the first time appeared on Mischief Reef. “A radar-carrying aerostat [blimp] would provide a very capable, but also a relatively cheap option for monitoring various activity around Mischief Reef, as well as potentially cueing surface-to-air and anti-ship missiles to engage potential threats,” Joseph Trevithick reported at The War Zone. The elevated position would help increase the overall range of the system substantially, which would be especially valuable for spotting low-flying threats, such as cruise missiles or swarms of small unmanned aircraft as they crest over the horizon. Though China is steadily improving the defenses on its man-made islands, low-flying cruise missiles certainly represent a continuing threat to its outposts.

Aerostat-mounted radar systems can also remain aloft for long periods and, depending on their exact capabilities, in many types of weather, making them far more cost-effective and easier to maintain than manned aerial sensor platforms. They can also fly much higher, and therefore have far longer line-of-sight to the horizon, than even large mast-mounted ground-based radars.

But an article in the latest edition of Naval and Merchant Ships, a Beijing-based monthly magazine, highlighted the artificial islands’ weaknesses in four areas: their distance from the mainland, small size, the limited capacity of their airstrips and the multiple routes by which they could be attacked. The magazine, published by the China State Shipbuilding Corporation, which builds ships for the Chinese navy, also warned that they had yet to achieve any significant offensive capabilities.

“These artificial islands have unique advantages in safeguarding Chinese sovereignty and maintaining a military presence in the deep ocean, but they have natural disadvantages in self-defence,” said the article. The magazine said the islands were deep in the South China Sea and far from the Chinese mainland. It also warned there was no coherent chain connecting them, so it would be difficult to provide support if one came under attack. “Take the example of the Fiery Cross Reef. It has a runway now, but it’s 1,000km (600 miles) away from Sanya city in Hainan province.” The distance means that China’s fastest combat support ships would need more than 20 hours to reach the island.

The article also argued that the islands were too far away to deploy the J-16, China’s most advanced multi-role strike fighter, effectively. The fighters could not patrol the area because of the distance and could be easily intercepted or attacked by surface ships. It continued that most of the islands only had one runway and did not have the space to provide the facilities to support more than one aircraft at a time. In the event of conflict, this means that a plane unloading or refuelling would have to stay on the runway at all times, preventing other planes from using it.

The airstrips are also close to the ocean, and the article said this left them exposed to damage from tides and tropical weather.

The magazine also said the artificial islands were too small to survive major attacks. Most of the islands are flat and have very limited vegetation or rocks. This means there is little cover against an attack and the best the Chinese military can do to protect equipment and supplies is build defensive shelters out of materials like steel – which has to be transported from the mainland and cannot withstand a sustained missile barrage.

The article also warned that nearby islands were held by rival claimants, and said that if the US supported allies such as the Philippines or Malaysia in any conflict, the were multiple approaches from which it could attack – such as the Philippine island of Palawan, to the east of the Spratlys, or the Strait of Malacca to the west.

And if a war does break out, these islands would be turned into craters. They do not affect U.S. naval power because they are small and their location is known. Neither satellites nor unmanned vehicles would be needed to locate them. Cruise missiles launched by air, sea or land could neutralize the islands rapidly.

Certainly, the Chinese could build air defenses, but as we have seen in Syria, shooting down cruise missiles doesn’t protect your position. Since any air defense system can be saturated by too many missiles, an attacking force could calculate how many missiles it will take to penetrate the system. And since cruise missiles are unmanned, the U.S. wouldn’t hold back out of fear of taking on casualties in the way it might if neutralizing the Chinese positions required manned aircraft.

During a briefing, Lieutenant General Kenneth McKenzie, director of the Joint Staff, told reporters that the US military had a great deal of experience in “taking down small islands” in the western Pacific, referring to America’s bloody “island-hopping” campaign against the Empire of Japan in World War II.

References and Resources also include:

International Defense Security & Technology Your trusted Source for News, Research and Analysis

International Defense Security & Technology Your trusted Source for News, Research and Analysis