Free-Space Optical Communication (FSOC) represents a radical departure from traditional radio-based systems, signaling a paradigm shift in how we imagine communication across the cosmos. Unlike conventional radio waves, FSOC uses visible and infrared light to transmit data through tightly focused beams of photons. Operating on the principle of line-of-sight, FSOC establishes an optical wireless link between a laser source and a detector, transmitting information through free space—whether air, outer space, or vacuum. This reliance on light rather than radio energy offers dramatic improvements in data rates and bandwidth, enabling high-capacity communication systems that are essential for modern and future applications.

Optical System Design

FSOC systems integrate highly specialized optics, transmitters, and receivers. Terminals typically include transmit, receive, acquisition and tracking, and reference channels. Spaceborne terminals use compact telescope apertures (5–50 cm), while ground-based receivers can extend up to 10 m to capture faint deep-space signals. Precision is critical: beam divergence must be measured in microradians, and pointing accuracy requires star trackers, beacon signals, and active stabilization. In addition, ensuring Transmit-Receive isolation is crucial, as outgoing laser power can overwhelm faint return signals without spatial, spectral, and polarization filtering.

Receiver and Detector Technology

Detectors define system sensitivity and ultimately determine achievable data rates. Traditional avalanche photodiodes offer simplicity but are less efficient compared to single-mode coherent receivers. Recent breakthroughs include photon-counting detectors that achieve near 1 photon-per-bit (PPB) sensitivity, demonstrated by NASA’s Lunar Laser Communication Demonstration (LLCD) at 622 Mbps. Future systems may employ superconducting nanowire detectors with >90% quantum efficiency, though cryogenic cooling remains a barrier. Advances in phase-sensitive optical amplifiers (PSAs) show promise for achieving theoretical noise-free performance at Gbps rates, marking a potential leap for long-haul interplanetary links.

Flight Optics, Pointing, and Tracking

Maintaining alignment between narrow laser beams across thousands—or millions—of kilometers is another formidable challenge. FSOC systems employ a combination of gimbaled telescopes, steering mirrors, Risley prisms, and inertial references to achieve sub-microradian precision. Acquisition is often aided by scanning techniques or cooperative beacon signals. In high-dynamic scenarios, a point-ahead mechanism is required, where transmitters aim slightly ahead of the receiver to account for relative motion—ranging from tens of microradians in Earth orbit to hundreds in interplanetary missions.

Overcoming Atmospheric Challenges

One of the central challenges in FSOC is its sensitivity to atmospheric conditions such as fog, rain, and smog, which can attenuate signals and increase the bit error ratio (BER). To counter these effects, developers have designed multi-beam and multi-path architectures that employ multiple transmitters and receivers to increase link resilience. In addition, advanced systems incorporate larger fade margins—essentially reserves of extra power—to help maintain stable connections during adverse weather.

Operating wavelength plays a crucial role in system performance. Devices using the 1550 nm wavelength achieve considerably lower optical losses than those operating at 830 nm, especially in dense fog conditions. These longer-wavelength systems can also transmit higher power levels while remaining eye-safe, usually falling under Class 1M safety standards. To further enhance reliability, advanced solutions such as EC SYSTEM continuously monitor link quality and dynamically adjust laser power in real time using automatic gain control. These measures are helping FSOC evolve from a vulnerable niche technology into a robust and dependable communication solution.

Reduction in SWaP: A New Era of Integration

The drive to reduce Size, Weight, and Power (SWaP) requirements has been a game-changer for FSOC. Earlier generations of systems relied on large, heavy optical benches, complex steering mechanisms, and power-hungry amplifiers. Today, fast-steering mirrors (FSMs) and optical closed-loop beacon tracking allow for precise beam alignment in compact designs. These breakthroughs have made it possible to build FSOC systems weighing less than 5 kg that can deliver data rates ranging from 10 to over 100 Gb/s with remarkable energy efficiency.

Such lightweight and efficient systems are now deployable in CubeSats and microsatellites, extending internet connectivity to remote and underserved regions without the need for expensive cabling infrastructure. Beyond satellites, SWaP-optimized FSOC designs are also being integrated into mobile military and commercial platforms, airborne systems, and terrestrial point-to-point connections. The deployment of laser-based intersatellite links in orbital constellations—“canopies of connectivity” surrounding the Earth—illustrates FSOC’s potential to deliver global broadband access and support the next generation of interconnected digital infrastructure.

Developments in FSOC

FSOC has already moved beyond theory, with successful demonstrations and operational deployments proving its reliability. Landmark projects such as SILEX (Semiconductor Laser Intersatellite Link Experiment), GOLD (Ground/Orbiter Lasercom Demonstration), and LADEE (NASA’s Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer) showcased its viability for space-based communications. Europe achieved another milestone with EDRS (European Data Relay System), also known as the SpaceData Highway, which became the first operational laser communication service, relaying Earth observation data at unprecedented speeds.

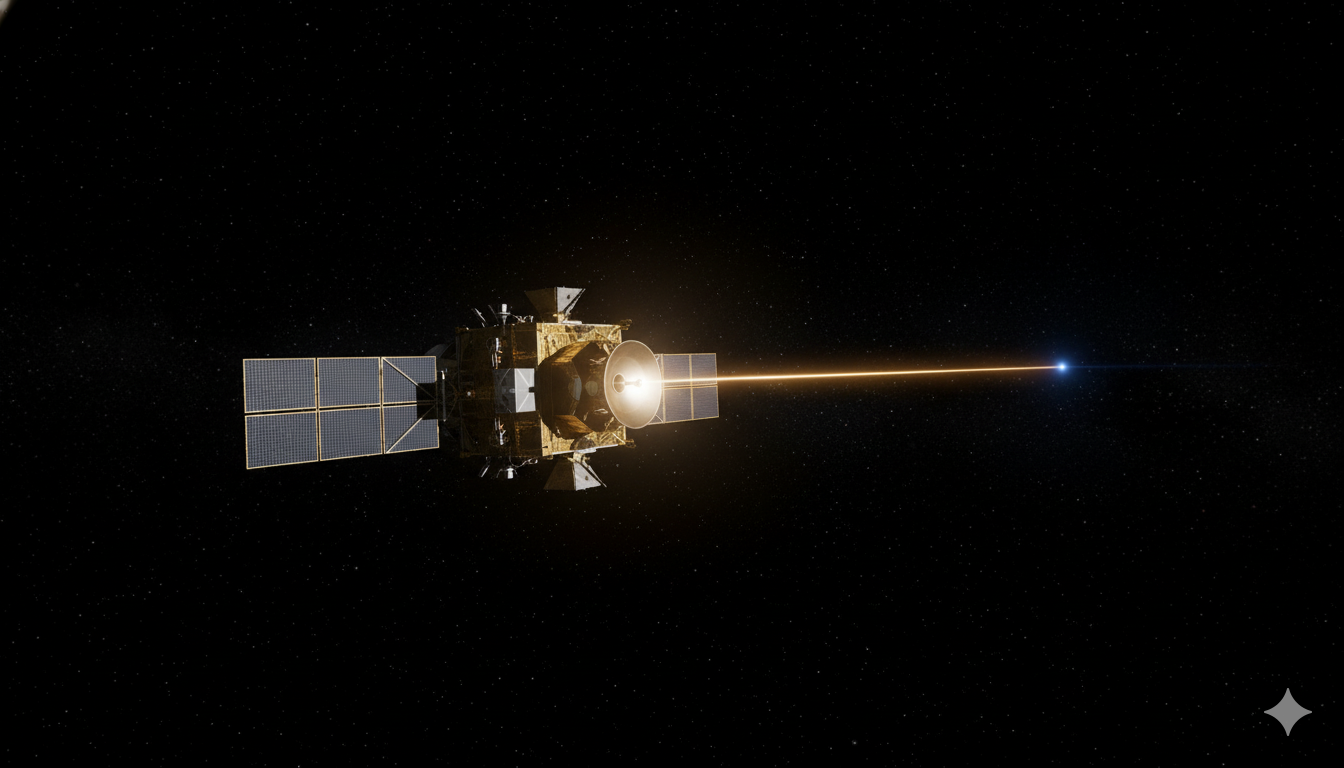

The most dramatic leap forward came with NASA’s Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) experiment, which achieved a “first light” by successfully transmitting laser data across nearly 10 million miles—40 times the distance between Earth and the Moon. Mounted on the Psyche spacecraft, DSOC used a near-infrared laser to exchange data with the Hale Telescope at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory. By “closing the link” between spacecraft and Earth, DSOC demonstrated that real-time, high-bandwidth communications with future Mars missions and beyond is within reach. This achievement marks the dawn of laser-powered deep space communication.

Looking ahead, DSOC will continue collecting performance data as Psyche travels toward the asteroid belt, refining optical communication technology for long-term use. The implications are profound: faster transmission of scientific data, real-time astronaut communication from Mars, and more efficient exploration of distant worlds. FSOC is thus transforming from experimental innovation into a cornerstone of interplanetary exploration

Emerging Breakthroughs

The evolution of FSOC is being accelerated by integrated photonics, which miniaturizes lasers, modulators, and switches onto microchips. NASA’s ILLUMA-T modem, set for deployment on the International Space Station, is an example of compact, high-rate FSOC hardware. Similarly, patented innovations in multi-channel beam pointing and tracking are eliminating heavy gimbals while improving accuracy. Even more futuristic are spacetime wave packets, a new class of laser beams that can defy traditional refraction rules, offering unprecedented control over signal propagation

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Despite its many advantages, FSOC still faces obstacles, including vulnerability to extreme weather, precise alignment requirements, and maintaining stability over long distances. To mitigate these challenges, researchers are pursuing hybrid communication models that combine FSOC with traditional RF systems, ensuring seamless connectivity during optical link disruptions. Adaptive optics and machine learning algorithms are being employed to correct turbulence-induced distortions in real time, further strengthening link stability.

In addition, NASA and other agencies are experimenting with integrated photonics. In 2020, NASA tested a photonics modem aboard the International Space Station, achieving data rates 10 to 100 times faster than conventional systems. These advances in sensitivity, beam control, and compact integration are pushing FSOC closer to maturity.

As these innovations continue to evolve, FSOC is poised to become the backbone of future communication networks. Its unmatched bandwidth, security, and scalability make it not just a complement to radio, but a foundation for both global telecommunications and interplanetary missions. By addressing challenges in reliability, miniaturization, and adaptability, FSOC is steadily advancing toward revolutionizing how humanity connects across Earth and the cosmos.