In the rapidly advancing world of quantum technologies—from ultra-precise atomic clocks to powerful quantum computers—light plays a pivotal role. Specifically, lasers operating in the visible and short near-infrared (NIR) range (400–1000 nm) have become indispensable tools, enabling everything from manipulating individual atoms to transmitting quantum information.

However, not all lasers are created equal. Quantum applications demand high stability, ultra-low noise, and extremely precise wavelengths, which traditionally required large, expensive, and energy-intensive laboratory systems. Today, a new generation of photonic integrated circuit (PIC) lasers is transforming this landscape, offering world-class performance on chips smaller than a fingernail and enabling robust, scalable quantum devices.

Why Visible and Short-NIR Lasers Are Quantum’s Secret Sauce

Lasers operating in the visible and short near-infrared (NIR) range (400–1000 nm) are uniquely suited to quantum technologies because of their strong and precise interactions with atoms and ions—the fundamental building blocks of many quantum processors and sensors. These wavelengths allow researchers to manipulate quantum states with high fidelity, making them essential for applications ranging from atomic clocks to quantum computing. In addition, visible and short-NIR lasers enable high-resolution spectroscopy and imaging, providing the precision required to probe ultra-narrow atomic transitions or detect subtle changes in quantum systems. Their ability to be frequency-doubled or otherwise wavelength-converted further expands their versatility, allowing compatibility with a wide range of quantum platforms and experimental setups.

The practical advantages of these lasers become particularly evident when considering real-world applications. For instance, teams developing rubidium-based quantum sensors historically relied on bulky 780 nm lasers that were confined to controlled laboratory environments. Such systems were not portable, limiting deployment in field applications where environmental conditions fluctuate. By transitioning to integrated photonic circuit (PIC) lasers, these same sensors have become compact, robust, and portable, enabling precise measurements of tiny magnetic field variations even in urban or outdoor settings. This shift demonstrates that integrated visible/NIR lasers are not merely miniaturized lab tools—they can operate reliably under real-world conditions.

Moreover, the move to integrated PIC lasers represents a broader trend in quantum technology: bringing laboratory-grade performance into practical, deployable devices. These lasers combine stability, low noise, and wavelength precision in a form factor small enough for portable quantum instruments. As a result, researchers and engineers can now envision field-ready quantum systems for sensing, navigation, and computing, bridging the gap between cutting-edge science and tangible applications. The ability to translate delicate quantum control into practical devices underscores why visible and short-NIR lasers are truly the “secret sauce” of the quantum revolution.

The PIC Revolution: Shrinking Lasers, Expanding Possibilities

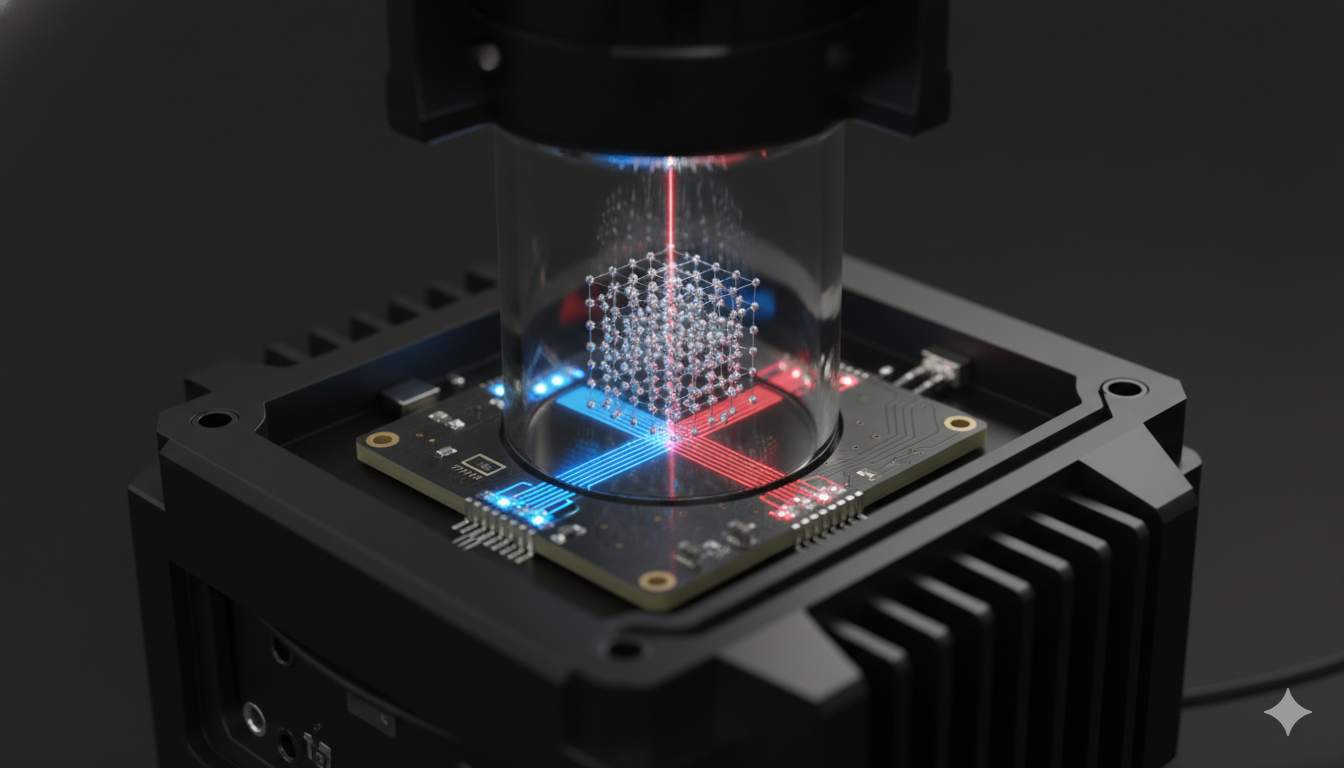

Photonic integrated circuits (PICs) represent a transformative shift in laser technology by consolidating all essential components—gain medium, resonator, modulators, and detectors—onto a single chip. This high level of integration drastically reduces system size, lowers energy consumption, and improves robustness against environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations or vibrations. Beyond these technical advantages, PICs enable scalable mass production, allowing manufacturers to produce quantum-grade lasers at a fraction of the cost and size of traditional benchtop systems.

The real-world impact of this technology is best illustrated through practical applications. In the development of portable atomic clocks, traditional systems relied on large benchtop lasers housed in climate-controlled laboratories, making field deployment nearly impossible. With PIC lasers, these atomic clocks have been miniaturized into suitcase-sized packages, retaining ultra-high precision while consuming far less power. This miniaturization has enabled deployment on ships, aircraft, and satellites, where they provide precise timekeeping and synchronization critical for navigation, communication, and defense systems.

Furthermore, the PIC revolution is opening doors for applications that were previously unimaginable due to the size and fragility of traditional lasers. By combining stability, efficiency, and portability, integrated lasers allow researchers to take lab-grade quantum systems into real-world environments without sacrificing performance. From portable quantum sensors monitoring environmental changes to scalable quantum computing setups, PIC lasers are turning complex laboratory experiments into deployable, practical technologies, marking a significant step toward the widespread adoption of quantum devices.

Key Building Blocks of Integrated Visible/NIR Lasers

To build high-performance visible and short-NIR lasers for quantum technologies, engineers rely on a combination of materials, architectural designs, and nonlinear optical techniques. Each of these building blocks addresses a specific challenge, from generating the right wavelength to ensuring stability, compactness, and reliability.

Hybrid and Heterogeneous Integration

No single material can satisfy all the requirements for a high-performance quantum laser. To overcome this limitation, researchers employ hybrid and heterogeneous integration, combining III-V semiconductors for optical gain, low-loss waveguides such as silicon nitride or thin-film lithium niobate for light confinement, and nonlinear materials for on-chip wavelength conversion. This approach allows each material to contribute its strengths, producing lasers that are efficient, stable, and capable of generating precise wavelengths for demanding quantum applications.

A concrete example comes from a quantum computing startup that integrated multiple laser lines on a single chip to control calcium ions at 674 nm, 790 nm, and 1030 nm. This design reduced system complexity, minimized alignment errors, and improved qubit gate fidelity, enabling a more scalable and robust platform. By using heterogeneous integration, the team created a multi-purpose laser system capable of supporting the complex requirements of trapped-ion quantum processors, demonstrating how these integrated architectures make high-performance quantum devices more practical and deployable.

Advanced Laser Architectures

Architectural innovations are equally crucial in integrated lasers. External-cavity lasers allow precise wavelength stabilization through on-chip mirrors and gratings, while self-injection locking leverages high-Q resonators to narrow linewidths and reduce noise. These innovations enhance the stability and fidelity of laser outputs, which are essential for precision quantum measurements and computations.

In practice, a research team developing a quantum gravimeter used self-injection-locked lasers to maintain high stability in outdoor environments, where temperature fluctuations and vibrations would normally disrupt lab-grade laser performance. With these advanced architectures, the gravimeter achieved precise underground density mapping, a measurement that would have been impossible with conventional bench-top lasers. This example highlights how innovative laser architectures not only improve performance in controlled labs but also extend quantum technologies into challenging real-world conditions.

Nonlinear Wavelength Conversion

Many quantum platforms require laser light at highly specific wavelengths that are not always directly accessible from standard gain materials. Integrated nonlinear optics address this challenge by enabling harmonic generation or optical parametric oscillation (OPO) to create new wavelengths on-chip, eliminating the need for bulky free-space optical setups.

For instance, a university lab doubled 1550 nm light to 775 nm to manipulate strontium atoms in optical clock experiments. By performing this wavelength conversion entirely on a single integrated chip, the researchers reduced system size, improved stability, and avoided the alignment challenges associated with free-space optics. This approach demonstrates how nonlinear conversion in PIC lasers allows highly specialized quantum experiments to be performed with compact, reliable, and deployable setups.

Quantum Applications Driving the Demand

Visible and short-NIR integrated lasers are not merely technological curiosities—they are the engines driving the most advanced quantum applications today. Their stability, precise wavelength control, and compact form factor make it possible to bring laboratory-grade quantum systems into practical, real-world environments, from ultra-precise timekeeping to next-generation sensing and quantum computing.

Optical atomic clocks, which surpass traditional cesium-based clocks by orders of magnitude, rely on lasers capable of probing ultra-narrow atomic transitions with exceptional stability. Using PIC lasers, researchers have miniaturized portable optical clocks based on strontium (698 nm) and ytterbium (578 nm) atoms. These systems, once confined to benchtop laboratories, now fit into suitcase-sized packages that maintain extraordinary precision while consuming significantly less power. They are being deployed on ships and satellites, providing highly accurate timekeeping for navigation, telecommunications, and scientific research—demonstrating how integrated lasers can transform precision instruments into field-ready tools.

Quantum sensors, which exploit the extreme sensitivity of quantum states to measure gravity, magnetic fields, or acceleration, also benefit from integrated lasers. NV-center diamond magnetometers, for example, use lasers to detect nanoscale variations in magnetic fields. With integrated PIC lasers, these sensors have become compact and portable, capable of functioning in urban and industrial environments where conventional lab systems would fail. Similarly, atom interferometers used for gravity mapping leverage narrow-linewidth, stable lasers to maintain coherence over long measurement periods, enabling applications such as underground resource mapping and environmental monitoring. These examples show how integrated lasers expand the reach of quantum sensing from controlled labs to the real world.

Quantum computing platforms, particularly trapped-ion and neutral-atom systems, require multiple lasers for cooling, trapping, and manipulating qubits, where precision and stability directly affect gate fidelity and computational performance. A trapped-ion system controlling calcium ions at 674 nm and 1030 nm demonstrates the advantage of integrated multi-wavelength PIC lasers: they replace bulky lab lasers, simplify the setup, enhance qubit fidelity, and make the platform more scalable. Neutral-atom systems manipulating rubidium (780 nm) and strontium (461 nm) atoms also leverage integrated lasers for cooling, state preparation, and readout in compact, deployable form factors. Together, these examples illustrate how integrated visible/NIR lasers are making high-performance quantum computing systems more practical, reliable, and ready for real-world deployment.

Recent Breakthroughs and Demonstrations

Recent years have seen remarkable advances in integrated visible and short-NIR lasers, bringing laboratory-grade performance to compact, deployable devices. Researchers and companies alike have achieved breakthroughs in linewidth stability, wavelength coverage, and output power, demonstrating that integrated photonics can meet the stringent demands of quantum technologies.

One notable achievement is the development of narrow-linewidth PIC lasers with linewidths below 1 kHz, rivaling traditional benchtop lasers. For instance, a team working on portable optical clocks demonstrated that such lasers could maintain ultra-high frequency stability even in field conditions. By miniaturizing the laser systems onto a chip, they reduced both power consumption and system size, enabling clocks to operate on ships and satellites without losing precision. This illustrates how integrated lasers are turning once-laboratory-bound quantum devices into practical, real-world instruments.

In terms of wavelength coverage, integrated lasers now span much of the visible spectrum, from blue (404 nm) to red (780 nm), enabling compatibility with a wide range of atomic and molecular quantum platforms. A quantum computing startup, for example, implemented multiple wavelengths on a single PIC chip to manipulate calcium and rubidium ions for trapped-ion operations. This multi-wavelength integration simplified experimental setups, improved gate fidelity, and enhanced scalability, showing how versatile integrated lasers can support complex quantum experiments.

Finally, power scalability has also advanced significantly, with chip-scale lasers now delivering hundreds of milliwatts of output—enough for most quantum sensing and computing applications. Companies like Vescent Photonics, PsiQuantum, and Xanadu are commercializing these technologies, while academic groups at NIST, TU Eindhoven, and UC Santa Barbara continue to push performance boundaries. From portable atomic clocks to deployable quantum sensors and scalable quantum computing platforms, these breakthroughs highlight the transformative potential of integrated lasers to make quantum systems practical, reliable, and ready for real-world applications.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite rapid progress, integrated visible and short-NIR lasers still face several challenges that must be addressed to fully realize their potential in quantum technologies. Combining multiple materials and functions on a single chip is inherently complex, and maintaining performance under real-world conditions requires careful design. For instance, multi-wavelength PIC lasers used in trapped-ion quantum computers must deliver precise, stable output for several atomic transitions simultaneously. Any misalignment or thermal drift can reduce qubit fidelity, highlighting the importance of robust integration techniques.

Power handling and heat dissipation present another hurdle. As chip-scale lasers deliver higher output powers, managing thermal effects becomes critical to prevent performance degradation. A practical example comes from portable atomic clocks: when scaling up laser power for field deployment, researchers had to design integrated thermal management solutions to maintain linewidth stability while operating in variable environmental conditions. Without effective thermal control, even the most advanced PIC lasers could fail to maintain the precision required for real-world applications.

Finally, packaging and system-level integration remain key challenges. Turning bare chips into user-friendly, deployable modules that include control electronics, cooling, and optical interfaces is essential for field-ready quantum devices. Multi-wavelength platforms, for example, must incorporate precise alignment, compact optics, and low-noise electronics to function outside the lab. As companies and research groups continue to innovate in packaging and reliability, integrated lasers are poised to move from experimental setups to robust instruments in portable atomic clocks, quantum sensors, and scalable quantum computing platforms. These developments suggest that, with continued refinement, integrated lasers will soon enable fully deployable quantum technologies across multiple industries.

Conclusion: Lighting the Path to Quantum Technologies

Integrated visible and short-NIR lasers are no longer confined to laboratory benches—they are the invisible engine driving the second quantum revolution. By combining compactness, stability, and wavelength versatility, these lasers are enabling quantum technologies that were previously impractical or impossible to deploy outside controlled environments. From portable atomic clocks and field-ready quantum sensors to scalable trapped-ion and neutral-atom quantum computers, integrated lasers are at the heart of each breakthrough.

Consider the case of portable optical clocks: chip-scale lasers allow entire timekeeping systems to fit into suitcase-sized packages while maintaining extraordinary precision, powering applications in satellite navigation and scientific research. In quantum sensing, NV-center diamond magnetometers and atom interferometers now operate in urban and industrial settings, mapping magnetic fields and gravity variations with unprecedented resolution. Quantum computing platforms, meanwhile, rely on multi-wavelength integrated lasers to manipulate ions and atoms with high fidelity, simplifying complex experimental setups and making scalable quantum processors feasible. These examples illustrate how integrated photonics is turning theoretical quantum advances into practical, deployable technologies.

Looking ahead, the continued refinement of integration techniques, thermal management, and packaging will unlock even more possibilities. As reliability improves and multi-wavelength platforms become standard, we can expect quantum systems to become ubiquitous in research, industry, and technology infrastructure. For engineers, researchers, and investors, the message is clear: the future of quantum technologies is built on integrated photonics, and the innovations happening today are lighting the path toward a quantum-enabled world.