As quantum technology accelerates, researchers are hunting for materials that can unlock unprecedented capabilities, from ultra-sensitive sensors to ultra-cold quantum computers. One such material—often overshadowed but increasingly vital—is helium-3 (³He).

This rare isotope of helium possesses unique quantum properties that make it invaluable for applications in quantum sensing, quantum computing, and advanced medical imaging. However, its scarcity and complex geopolitical implications create significant challenges for the future of quantum innovation.

What Makes Helium-3 Special?

Unlike its more common counterpart helium-4, helium-3 is a fermion. This means its atoms obey the Pauli exclusion principle, leading to extraordinary behavior at ultra-low temperatures. In such extreme conditions, helium-3 can become superfluid, flowing without viscosity and enabling breakthroughs in cryogenics.

Its atomic structure also makes it remarkably sensitive to magnetic fields, a property that is essential for cutting-edge quantum sensors. Furthermore, helium-3 has an exceptional ability to absorb neutrons, making it useful for nuclear detection systems and certain forms of medical imaging. These distinctive characteristics position helium-3 as a crucial enabler in several advanced quantum applications.

Quantum Applications Driving Demand

One of the most prominent uses of helium-3 is in ultra-sensitive quantum sensors. Devices such as Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices (SQUIDs) and spin-based magnetometers leverage helium-3 to detect extraordinarily weak magnetic fields. This capability can be applied in diverse areas—from mapping brain activity through magnetoencephalography (MEG), to detecting mineral deposits for sustainable mining, to enhancing security screening systems for nuclear materials.

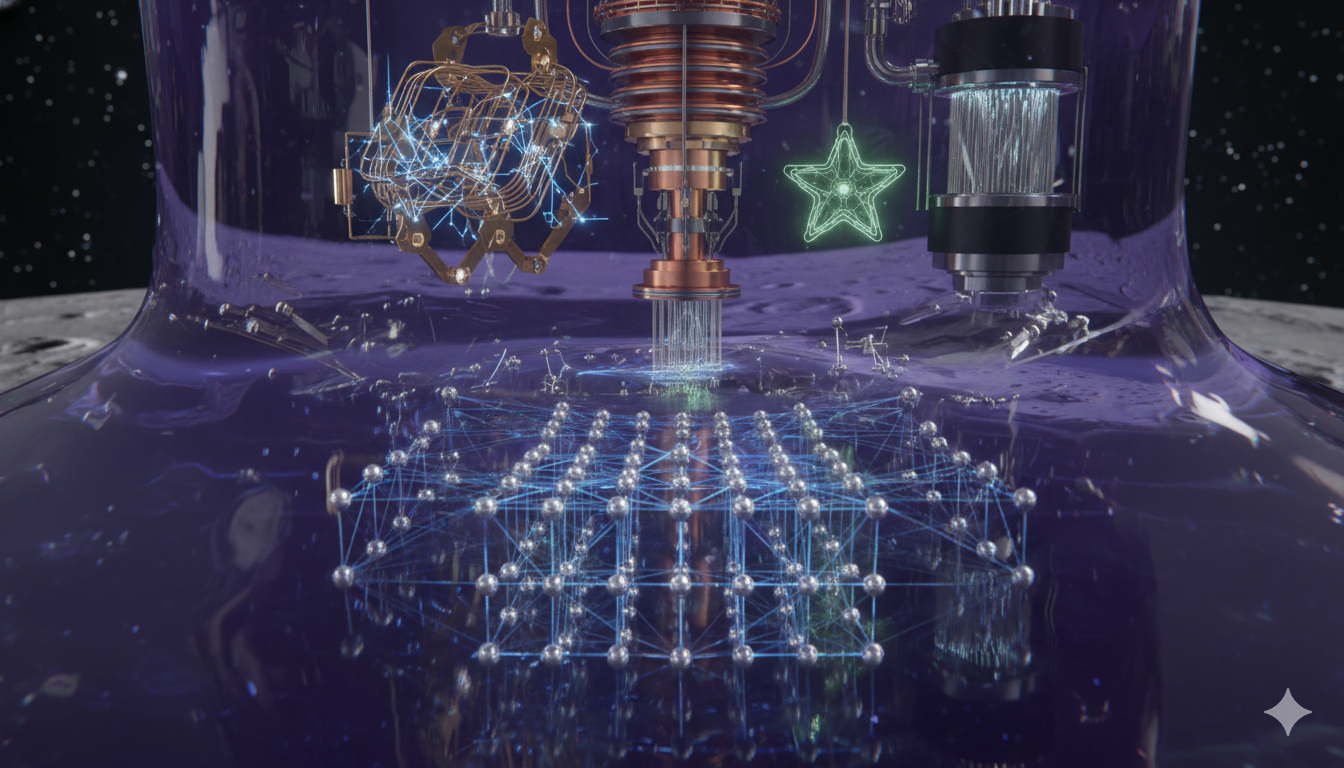

Helium-3 is also integral to the cooling systems of quantum computers. Quantum processors operate best at temperatures near absolute zero, and while most dilution refrigerators rely on helium-4, helium-3 enables even lower cooling thresholds. This can improve qubit stability and extend coherence times, directly impacting the reliability and scalability of quantum computation.

In medicine, helium-3 plays an important role in non-invasive lung imaging. Hyperpolarized helium-3 gas used in MRI scans allows doctors to visualize the airflow inside the lungs with exceptional clarity, aiding in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary diseases. Beyond healthcare, its neutron absorption capabilities make it a critical component in detectors for nuclear safeguards and anti-terrorism measures.

The Energy Promise: Helium-3 and Nuclear Fusion

Perhaps the most visionary application of helium-3 lies in its potential to fuel aneutronic nuclear fusion—a form of fusion that produces energy without the harmful neutron radiation associated with traditional fusion reactions. When fused with deuterium, helium-3 could generate enormous amounts of clean electricity with minimal radioactive waste and without the risk of a chain reaction meltdown.

Such a breakthrough would transform the global energy landscape, providing a virtually limitless source of power while addressing climate change and reducing dependence on fossil fuels. The challenge is that current fusion reactors capable of using helium-3 are still in the experimental stage, and the isotope’s extreme scarcity remains a major barrier to commercial viability.

Scarcity and Supply Risks

Helium-3 is extremely rare on Earth. The majority of current supplies are obtained from the decay of tritium, itself a byproduct of nuclear weapons programs. The only other significant known source is extraterrestrial: the Moon’s surface contains helium-3 deposited over billions of years by the solar wind.

Global production is estimated at just 30 to 50 kilograms per year, and as quantum technologies scale, demand could rapidly outpace supply. This scarcity has driven costs to exceed $2,000 per liter and intensified geopolitical competition over existing reserves. Research into substitutes—such as helium-4-based dilution techniques and solid-state sensor materials—is underway, but none yet fully match helium-3’sunique properties.

Securing the Future Supply Chain

If quantum technology is to fulfill its potential, ensuring a reliable helium-3 supply will be essential. In the near term, increasing tritium recycling could help extract more helium-3 from existing nuclear stockpiles. In the longer term, space exploration—particularly lunar mining—offers a potentially vast but logistically complex source of the isotope.

Parallel to these efforts, scientists are working on alternative materials and methods to reduce dependence on helium-3 altogether. Advances in spin qubits based on silicon, or innovative approaches to quantum sensing and cooling, could eventually provide sustainable replacements.

Conclusion: A Resource Worth Watching

Helium-3 may not enjoy the public recognition of qubits or superconductors, but its role in quantum sensing, quantum computing, advanced medical imaging, and potentially fusion-based clean energy is irreplaceable—at least for now. As both the quantum industry and the search for sustainable energy intensify, securing a stable helium-3 supply will be as crucial as developing the technologies themselves.

Whether through recycling, lunar exploration, or the invention of new materials, our management of this rare isotope could shape the trajectory of both quantum science and global energy production for decades to come.