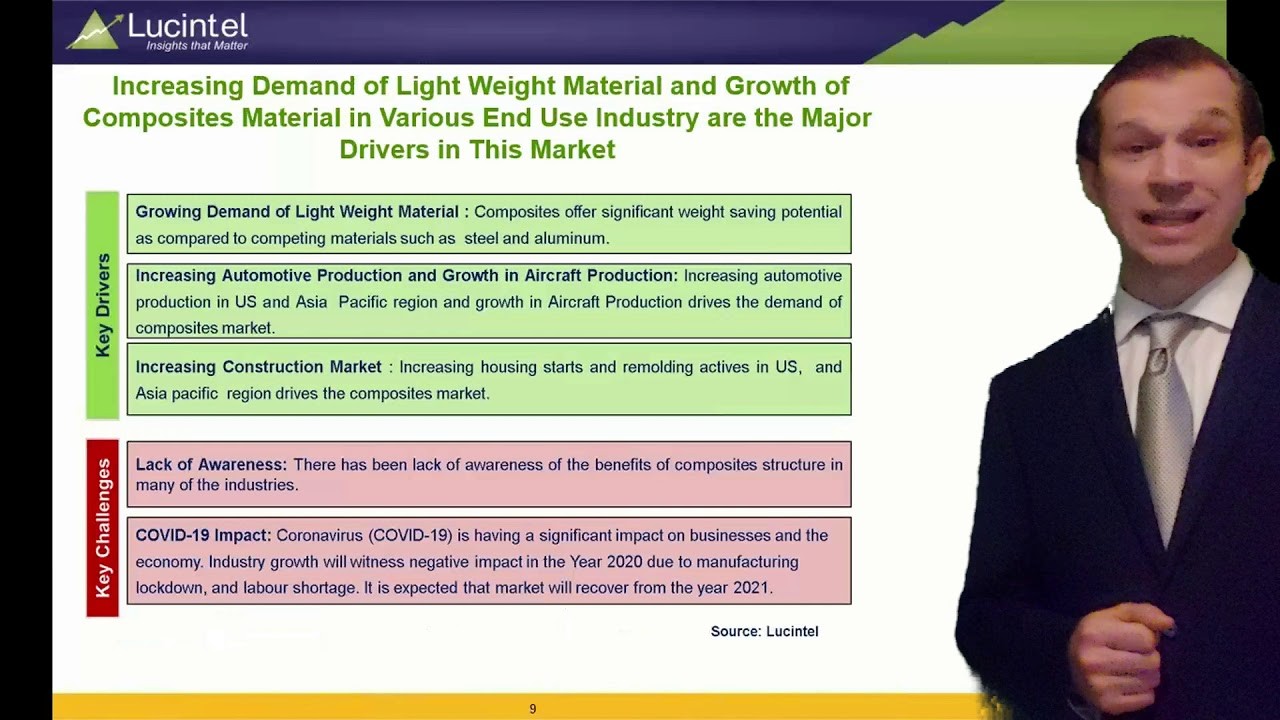

According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the demand for air travel rose by 7.4% in 2018 from 2017 levels. Air passengers accounted for 81.9% of the load factor on aircrafts, while freight load was 49.3%, the IATA data reveals. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has created turmoil in the global economy. One of the…