For decades, radio frequency (RF) communication has been the lifeline of space exploration. From the faint signals of Sputnik to the continuous data streaming from the Perseverance rover on Mars, radio waves have carried humanity’s voice into the cosmos. But as our missions grow more ambitious—high-definition video from the Moon, vast sensor datasets from asteroids, and real-time telemetry from the outer planets—the bandwidth of RF communication is becoming a serious bottleneck.

We now stand at the dawn of a new era in space communications. Free-Space Optical Communication (FSOC), which transmits data using focused beams of light rather than radio waves, promises to break these limits and open a superhighway of information across the solar system.

The RF Bottleneck: Why We Need a Faster Cosmic Internet

The existing methods of deep space communication rely heavily on radio-frequency (RF) signals, which have served us well for decades. However, RF communications have limitations, such as low data rates and narrow bandwidth. Spacecraft typically have relatively weak receivers, necessitating the transmission of strong radio signals from Earth. These signals are not only demanding in terms of power but also require large sensitive radio dishes to capture the spacecraft’s relatively weak replies. This is why NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN), a collection of specially designed radio telescopes, plays a crucial role in enabling deep-space communication.

For more than half a century, the Deep Space Network (DSN)—a globe-spanning array of giant radio antennas—has been the backbone of communication between Earth and our spacecraft. It has carried signals from the Apollo missions, relayed breathtaking images of distant planets, and kept explorers like Voyager connected with us across billions of miles. Yet, as heroic as its service has been, the limitations of radio frequency (RF) communication are now holding back the pace of exploration.

One of the most pressing issues is low data rates. RF signals operate at relatively low frequencies, which limits the amount of information they can carry at once. A single high-resolution image from Mars can take hours to download, slowing the work of scientists who need rapid access to mission data. As spacecraft instruments become more advanced and capable of capturing richer datasets, this narrow information pipeline simply cannot keep up.

Another growing challenge is spectrum congestion. The radio spectrum has become a crowded highway, with countless terrestrial services—including mobile networks like 5G, satellite internet, and broadcasting systems—competing for limited bandwidth. Deep space missions must carve out their share of this spectrum, but the competition is only intensifying, adding friction to already complex operations.

Finally, RF communication demands large and power-hungry infrastructure. Because radio signals spread widely and weaken over distance, capturing faint transmissions from deep space requires massive antennas spread across the Earth. Maintaining these facilities is costly and logistically demanding, and their sheer scale makes them difficult to expand in line with growing data demands.

As mission payloads evolve—streaming 4K video from the Moon, hyperspectral imagery of asteroids, and vast sensor datasets from Mars—the traditional RF pipeline is stretched beyond its limits. What space exploration needs now is not just incremental improvement but a quantum leap in capability—a new communication paradigm powerful enough to meet the demands of a data-rich era of discovery.

When we return to the Moon and place our first footsteps on Mars, we will want not only scientific data but live video feeds, high-resolution images, and even tweets from the astronauts. Increased space exploration and the growing capability and thus data output of satellite-borne sensors operated by agencies such as NASA, ESA and JAXA impose greater demands on communication systems to operate at higher data rates and to reach across farther distances into space. Even the most sophisticated radio network isn’t capable of that level of bandwidth. To address the growing demands of long-distance communication, a groundbreaking technology has emerged: Free Space Optical Communications (FSOC).

The Laser Solution: Trading Radios for Photons

Free-Space Optical Communication (FSOC) marks a radical departure from traditional radio-based systems. Instead of broadcasting broad radio waves, FSOC harnesses the power of tightly focused, invisible infrared lasers to encode information into streams of photons. In essence, it trades radio energy for light energy, opening the door to an entirely new era of space communication.

Operating on the line-of-sight principle, FSOC uses a laser at the source and a detector at the destination to create an optical wireless communication link through free space—whether that be the air, outer space, or the vacuum between planets. Unlike fiber optics, which rely on solid glass cables, FSOC transmits data directly through open space, enabling high-speed, high-capacity communication across vast distances.

This innovative approach delivers several groundbreaking advantages: massive bandwidth, greater efficiency, enhanced security, and the ability to shrink hardware for space missions. More importantly, the shift from radio to light is not just an incremental improvement—it is a paradigm shift in how humanity will connect across the cosmos, laying the foundation for interplanetary networks that can support the future of exploration, science, and even commerce beyond Earth.

One of the most significant advantages of FSOC is its unprecedented bandwidth. Laser light operates at frequencies nearly 10,000 times higher than those used in RF communications. This enormous jump in frequency translates into a much wider data pipeline, enabling spacecraft to transmit gigabytes of information in minutes rather than days. For scientists on Earth, that means faster access to high-resolution images, complex sensor data, and even real-time video from distant worlds.

Another compelling feature of FSOC is its operation in the license-free spectrum. Unlike traditional radio communication, which often demands the allocation of specific radio spectrum frequencies, FSOC operates in a spectrum that is free from regulatory constraints. This not only simplifies the implementation of FSOC systems but also reduces the bureaucratic hurdles often associated with obtaining the necessary spectrum licenses.

Laser communication also offers enhanced security. Unlike radio signals, which radiate outward in broad patterns that can be intercepted or jammed, a laser beam is extremely narrow and precise. This makes it far more resistant to eavesdropping or interference, ensuring that sensitive scientific and even military communications remain secure. In an era where information is as valuable as fuel, this built-in protection is a game-changing advantage.

Finally, FSOC is smaller, lighter, and more efficient than comparable RF systems. Traditional deep space communication requires massive antennas and high power levels, both on Earth and on spacecraft. In contrast, optical terminals are compact and energy-efficient, reducing the burden on spacecraft where every gram of mass and every watt of power is precious. For missions where payload capacity is tightly constrained, this efficiency can make the difference between a feasible design and an impossible one.

By replacing radio waves with beams of light, FSOC opens the door to a faster, more secure, and more efficient future of space exploration—one where data no longer trickles across the void, but flows at the speed of light.

From Terrestrial FSO to Interplanetary DSOC

Free-Space Optical (FSO) communication was originally developed to address limitations of fiber and radio networks on Earth, offering high-capacity, cable-free data links through laser beams. These systems had to contend with atmospheric interference, alignment challenges, and safety regulations, which drove innovations such as the use of 1550 nm lasers, multi-beam redundancy, and automatic gain control to stabilize connections. While designed for terrestrial needs, these solutions laid the groundwork for something far bigger: deep space communications.

NASA’s Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) project adapts and scales these Earth-tested innovations to the cosmic stage. Instead of spanning a few kilometers between rooftops, DSOC must maintain links across millions of miles, where spacecraft travel at thousands of miles per hour. Precision pointing, acquisition, and tracking systems—refined from terrestrial FSO experience—now enable nanoradian accuracy to lock a laser beam onto a moving target from interplanetary distances.

The parallels are striking: just as 1550 nm proved effective in reducing fog losses on Earth, similar near-infrared wavelengths are being used in space for low-loss, high-capacity transmission. Likewise, terrestrial redundancy techniques inspire hybrid DSOC networks that combine optical relays, adaptive power control, and RF backup links to ensure resilience. On Earth, these measures deliver reliable broadband; in space, they are powering video streams, engineering data, and scientific discoveries beamed back from tens of millions of miles.

Ultimately, the transition from terrestrial FSO to DSOC represents a seamless continuum of light-based communication. What began as a way to bypass fiber constraints in cities is now enabling humanity’s interplanetary internet, connecting Earth with the Moon, Mars, and beyond. The same principles that kept laser links steady across foggy skylines are now helping us stream the cosmos in real time.

Free Space Optical System

A Free Space Optical (FSO) communication system is a highly integrated setup that combines advanced optical transmitters and receivers, space-qualified steerable telescopes, and precise beam-stabilization mechanisms. Since the strength of optical communication lies in its narrow, tightly focused beams, the system must maintain extraordinary accuracy to ensure that the signal remains locked between transmitter and receiver, even across vast distances.

To achieve this, optical communication links typically employ several distinct channels, each serving a critical role: Transmit, Receive, Acquisition and Tracking, and Reference (Align) channels. The transmit channel carries laser-generated data through the exit aperture, while the receive channel collects incoming optical signals and directs them to a photodetector. Acquisition and tracking channels make use of beacon signals—either from cooperative sources like another spacecraft or natural references such as stars, the Moon, or the Sun-illuminated Earth—to maintain lock on the target. The reference channel, meanwhile, captures a portion of transmitted light to monitor and align the system without requiring high imaging fidelity.

Different mission scenarios demand varying optical system configurations. Flight terminals mounted on spacecraft typically employ telescope apertures between 5–50 cm in diameter, optimized for weight and compactness. Ground receiver terminals, by contrast, may require massive apertures of 0.5–10 meters to capture faint, long-distance signals. Additionally, uplink command systems or beacon transmitters use apertures of 0.5–1 meter to send strong reference beams back to spacecraft, enabling precise two-way communication.

A major design challenge is ensuring Transmit-Receive Isolation, since transmitted laser power can be many orders of magnitude stronger than the faint returning signals. Without careful engineering, scattered light from the transmit channel could overwhelm the sensitive receiver. In scenarios where transceivers must operate near the Sun, up to 150 dB of isolation may be necessary. Engineers mitigate this through a combination of spatial, spectral, temporal, and polarization isolation strategies, as well as coding techniques with deep interleaving.

Accuracy in pointing is further enhanced by dedicated star trackers, which act as acquisition and tracking beacons. Though small (typically 6–8 cm apertures), these trackers provide wide fields of view spanning several degrees, helping the system achieve sub-microradian pointing accuracy. Such precision is crucial when targeting distant spacecraft moving at thousands of miles per hour relative to Earth.

Finally, maintaining mechanical, thermal, and temporal stability is essential for long-term reliability. Lightweight telescope structures must resist deformation under thermal gradients, while differences in thermal expansion between optical and structural materials must be carefully managed. Any mechanical instability or thermal mismatch can distort the optical surfaces and degrade performance. Thus, FSO systems are designed to balance structural integrity, thermal control, and minimal mass—ensuring consistent high-quality communication across Earth’s atmosphere and the vacuum of space.

From Theory to Reality: Breakthrough Demonstrations

Far from being science fiction, laser communications have already been successfully tested and demonstrated:

NASA’s DSOC (Deep Space Optical Communications).

Riding aboard the Psyche spacecraft, DSOC recently achieved “first light,” beaming data from millions of miles away with record-breaking precision. Managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the system includes a flight laser transceiver and two powerful ground stations: the historic 200-inch Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory for downlink, and the Table Mountain Facility for uplink, capable of transmitting up to 7 kilowatts of laser power.

In December 2023, DSOC made history by transmitting the first-ever ultra-high-definition video from deep space—a playful compilation of team artwork, pet photos, and television test patterns—streamed from 19 million miles away. Even at distances of 33 million miles, the system achieved broadband-like speeds, confirming that FSOC can deliver up to 100 times the data rates of traditional RF communication.

As Meera Srinivasan, operations lead at JPL, noted:

“Laser communication requires a very high level of precision, and before Psyche launched, we didn’t know how much performance degradation we would see at our farthest distances. These results confirm that optical communications stand as a robust and transformative means of exploring the solar system.”

ESA’s EDRS (European Data Relay System).

Often called the “SpaceDataHighway,” EDRS is the world’s first operational laser relay system in geostationary orbit. It can transmit data from low-Earth orbit satellites to Earth at speeds up to 1.8 Gbps, turning what once took hours into near-real-time communication.

LLCD (Lunar Laser Communication Demonstration).

In 2013, NASA’s LLCD mission proved that high-speed laser comms were viable even across lunar distances. It achieved download rates of 622 Mbps from the Moon—faster than most Earth-bound broadband services at the time.

These demonstrations show that FSOC is not only viable but also scalable, laying the foundation for a communication revolution across the solar system.

China Advancements

China is actively advancing its free-space laser communication (FSLC) capabilities to support its ambitious interplanetary exploration goals, including missions to the Moon and Mars. Recognizing the limitations of traditional radio-frequency systems for deep-space communication, Chinese researchers and agencies have developed and tested laser communication technologies designed to handle the vast distances and high-data-rate demands of future missions. For instance, China’s lunar and Martian programs have incorporated optical communication experiments to enable high-speed data transmission between spacecraft, orbiters, and Earth-based stations. These efforts are critical for supporting crewed missions, robotic explorers, and eventual lunar or Martian bases, where real-time communication and large-volume data transfer—such as high-resolution imagery, video, and scientific data—are essential for mission success and operational safety.

The application of FSLC in China’s interplanetary strategy aims to ensure reliable, low-latency communication across millions of kilometers, facilitating not only command and control but also enhanced scientific returns and public engagement. Technologies tested on missions like the Chang’e lunar probes and Tianwen-1 Mars mission have demonstrated China’s capacity to implement laser communication in challenging environments, laying the groundwork for more sophisticated systems. Looking ahead, China plans to integrate FSLC into its planned lunar research station and future Mars sample-return missions, highlighting its commitment to establishing a robust, high-throughput communication infrastructure that can support sustained human and robotic activity beyond Earth. This focus on optical communication underscores China’s intent to be a leader in the next era of space exploration, where seamless connectivity is as vital abroad as it is at home.

Conquering the Challenges: Precision and Weather

As promising as laser communications are, they also introduce new engineering hurdles that must be overcome before FSOC can become the backbone of interplanetary communication. Two challenges stand out above the rest: precision and the atmosphere.

The first is the need for extreme precision. Unlike radio waves, which spread out and can still be detected even if the signal drifts slightly off course, laser beams are incredibly narrow and unforgiving. Pointing one from a spacecraft moving thousands of miles per hour to a receiver on Earth requires near-perfect accuracy. Engineers compare the task to hitting a moving dime from across a continent while both the shooter and the target are in motion. Achieving this level of stability depends on sophisticated Pointing, Acquisition, and Tracking (PAT) systems that can lock onto a target and maintain alignment despite the constant motion of spacecraft and Earth itself.

The second major obstacle is atmospheric interference. Unlike the vacuum of space, Earth’s atmosphere is filled with clouds, fog, and turbulent air that can scatter or distort laser signals. A clear line of sight is essential for reliable performance. To mitigate this, engineers are developing hybrid communication systems. In deep space, lasers provide fast, direct links between spacecraft and relay satellites, unaffected by weather. Closer to Earth, however, the final hop is routed through a global network of strategically placed ground stations located in dry, high-altitude regions with stable weather conditions. This approach ensures that even when one ground station is clouded over, another can pick up the signal without interrupting the data stream.

The Future is Photonic: Building a Networked Solar System

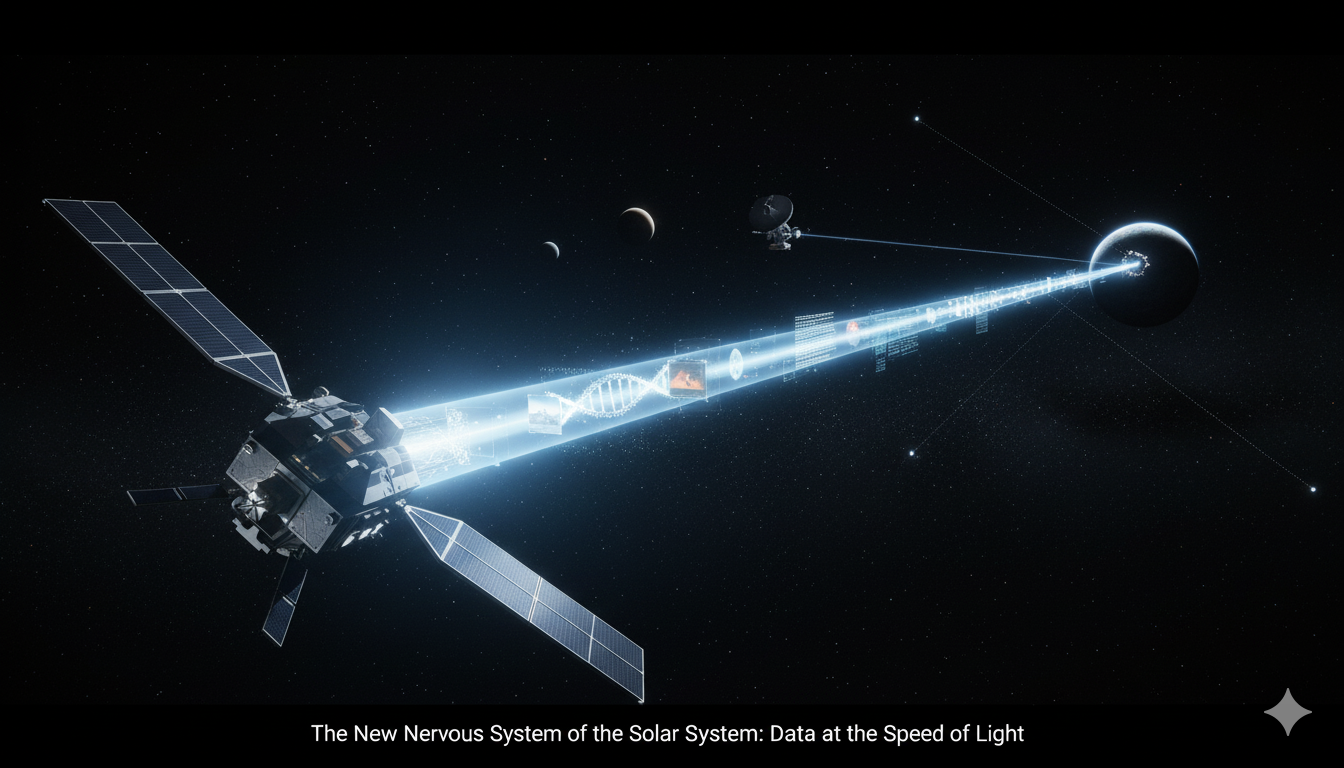

The ultimate promise of Free-Space Optical Communications is nothing less than a fully interconnected “Interplanetary Internet”—a web of light that links planets, spacecraft, and habitats across the solar system. What radio waves enabled for global communication on Earth, lasers could achieve on a planetary scale.

One of the most compelling near-term applications is in Mars missions. Astronauts exploring the Red Planet will need to transmit vast amounts of scientific data—ranging from geological analyses to high-resolution imagery—back to Earth. FSOC would allow them to send not just raw data but also immersive ultra-high-definition video and even virtual reality feeds. Scientists could virtually “stand” on the Martian surface, while the public could share in the adventure in unprecedented ways, narrowing the psychological gap between Earth and Mars.

Closer to home, NASA’s Lunar Gateway will serve as a proving ground for this technology. Planned as a vital outpost orbiting the Moon, the Gateway will test high-speed FSOC links between Earth, lunar astronauts, and spacecraft moving deeper into space. These experiments will help lay the communications foundation for permanent lunar bases and, eventually, missions beyond.

Meanwhile, back in Earth orbit, satellite mega-constellations are already pioneering laser communication. Companies are equipping satellites with laser inter-satellite links, creating resilient, high-speed mesh networks in space. These optical constellations can deliver global broadband, relay data at near-instantaneous speeds, and support real-time Earth observation. The lessons learned here will directly inform how we scale FSOC into deep space.

As these systems mature and expand, they will eventually weave together a solar system–wide web of light—a network supporting not only exploration but also commerce, defense, and even tourism beyond Earth. From lunar mining operations and Martian colonies to asteroid prospecting and space-based industries, every future frontier will depend on a backbone of laser-powered communication.

Conclusion: Lighting the Way Forward

The shift from radio waves to laser beams represents far more than a technical upgrade—it marks the foundation of humanity’s next great leap into the cosmos. Free-Space Optical Communication is not simply about faster data; it is about creating the nervous system of an interplanetary civilization. By enabling the near-instant transfer of vast datasets across unimaginable distances, FSOC ensures that we can see, analyze, and share the universe with a clarity once thought impossible.

NASA’s recent Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) milestone demonstrates that this vision is no longer theoretical. Successfully transmitting video, imagery, and scientific data across tens of millions of miles at broadband speeds proves that laser communication is operationally transformative. It opens the door to Mars expeditions, deep-space probes exploring the outer planets, and even the first precursors of interstellar travel.

With each beam of light carrying discoveries across the void, the cosmos itself seems to draw nearer. The future of exploration will not echo with radio static but instead shine with streams of light—a luminous bridge connecting Earth to every new horizon we reach.